Chapter 2

2 Piano Roll

Piano roll, perforated paper for a player piano, was invented in the late 19th century. A player piano is an elaborate version of a music box or a music machine.

The recording process is as follows. To make a recording of a piano playing, you put a long sheet of paper on a specially designed device and roll it up by turning it at a constant speed. When a pianist plays the piano, the sound comes out as normal and the recording machine perforates the roll of paper with numerous tiny marks that reflect his/her touch on the keyboard. This is the original media of the recording. When the performance is over, you remove the paper roll from the device and a craftsman makes rectangles of various sizes on the marks with a chisel. The finished product is a roll with a lot holes. Each company has a different manufacturing method, which will be discussed below.

To play back the performance, the perforated roll of paper is placed in a player piano. The player piano makes a sound each time it “reads” a hole and the hammer for the corresponding key is pushed up by air pressure and hits the string. In this way, the piano roll reproduces the acoustic piano sound. While the tempo was often not as accurate as that of a record, the sound was much better than that of a gramophone. This is why the player piano survived long after the use of gramophones became widespread. The modern digital piano uses electric means instead of a paper roll and records the player’s touch on the keyboard instead of the sound itself. It can also reproduce a performance on the spot. In contrast, the player piano with a piano roll actually hits its hammers, so the keys move as if an invisible person is playing the piano.

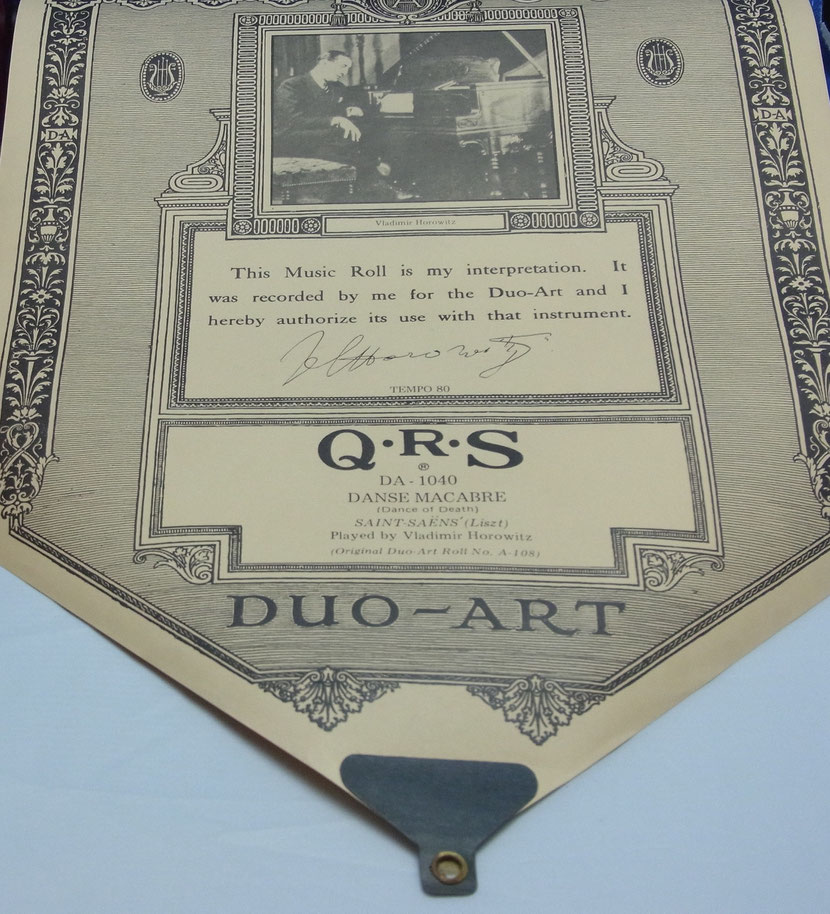

As each hole is made by a craftsman, the reproduced music is different from the real rendition. So in many cases, the pianist was asked to listen to the playback and fine adjustments were then made to the size and position of some of the holes. If the fine-tuning was satisfactory, she or he would sign the roll and it became an original recording.

Piano roll signed by Horowitz

Then the roll was mechanically duplicated, and in the case of Duo-Art, the copies would be sold with the performer’s photograph. The start of the roll is triangular in shape with a hook on the edge to fix the roll in place during playback.

The performances of numerous composers were recorded on piano rolls in the nineteenth century. For example, we can still listen to Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Saint-Saëns, Rachmaninoff, Richard Strauss, Grieg, and Scriabin play the piano. Unfortunately, Chopin, Mozart and Beethoven did not record their performances on piano rolls.

It was Edison’s phonograph that first enabled the sounds, voices and music of the past to be stored and played back, but the player piano was another epoch-making innovation in the history of mankind in that it enabled musicians to record and reproduce their performances. We have no access to the sounds, voices and music that existed before Edison. A music score is merely a record of the music’s notation. We can understand Chopin’s music through his scores, but it does not reveal anything about his own performance.

Originally, listeners had no option but to place a piano roll on a player piano. Such performances were not released on 78s or 45s (some were allegedly available on 78s, but there is no proof of this). LPs became available in 1951, but it was in the 1970s that the music on piano rolls was reproduced on LPs for the first time. Now such performances from the early days are also available on many CDs.

The following are examples of piano rolls that were re-released on LP:

1. Great Masters of the Keyboard (Columbia Records, USA, ML4291-95, 5 LPs)

2. Composers Playing Their Own Works—In Memory of Great Pianists (Telefunken, Japan, MY5001-3, 3 LPs)

3. Musikalische Dokumente (Telefunken, Germany, WE28000-24, 25 LPs)

4. Distinguished Recordings (DR101-6, 6 LPs)

5. The Golden Age of Piano Virtuosi (Argo Records, UK, DA41-3, 3 LPs)

6. Archive of Piano Music (Everest, USA, X901-26, 26 LPs)

7. The Keyboard Immortal Series (Superscope, USA, Kbi, A001-12, 12 LPs)

8. The Great Pianists of the Century (CBS Sony, 25AC241-7, 7 LPs)

9. Welte-Mignon 1905 (Telefunken, Germany, 6.35016, 5 LPs)

10. Klavier Keyboard Series (German, KS………… 30 LPs?)

11. Legendary Masters of the Piano (USA? …….. 3 LPs)

12. Piano-Roll Collection (from Duo-Art) (Columbia Records, Japan, GZ-7080-84, 5 LPs).

These LPs are reproductions of numerous composers’ performances (mostly playing their own music) that were originally recorded on piano rolls. Of course, we cannot listen to Chopin, Mozart and Beethoven play their own music on piano rolls, but as Edison invented the phonograph in the last days of Brahms and Tchaikovsky, the voice of Tchaikovsky and the voice and piano performance (Hungarian Dance) of Brahms were recorded on Edison’s wax cylinder. This is now available on CD (The Creators, Membrane Music, Germany, 232598).

Not just composers, but numerous pianists have left us their renditions on piano rolls. Among them are Busoni, Paderewski, Cortot, Rubinstein, Schnabel, Hofmann and Horowitz.

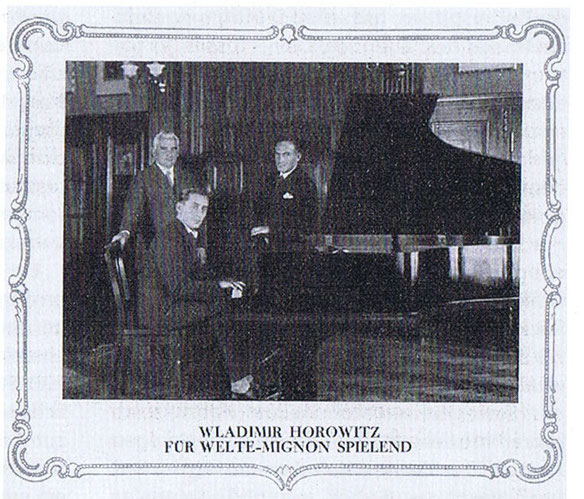

Horowitz made 12 piano rolls in 1926 under a contract with a German recording company, Welte-Mignon, and seven more in 1928 under a contract with a US company, Aeolian (Duo-Art). There were other manufacturers that produced piano rolls, but they were the only companies with which Horowitz worked.

Most of these piano rolls have been re-released on LPs, but in 2008 a German label, TACET, released CDs that contained all his performances from Welte-Mignon. Since then, we have been able to access all of Horowitz’s piano rolls (including Duo-Art) on CD.

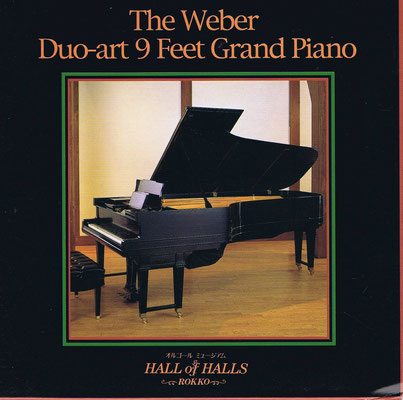

Museums of music boxes in Japan usually have player pianos and piano rolls, some of which are recorded and released on CD.

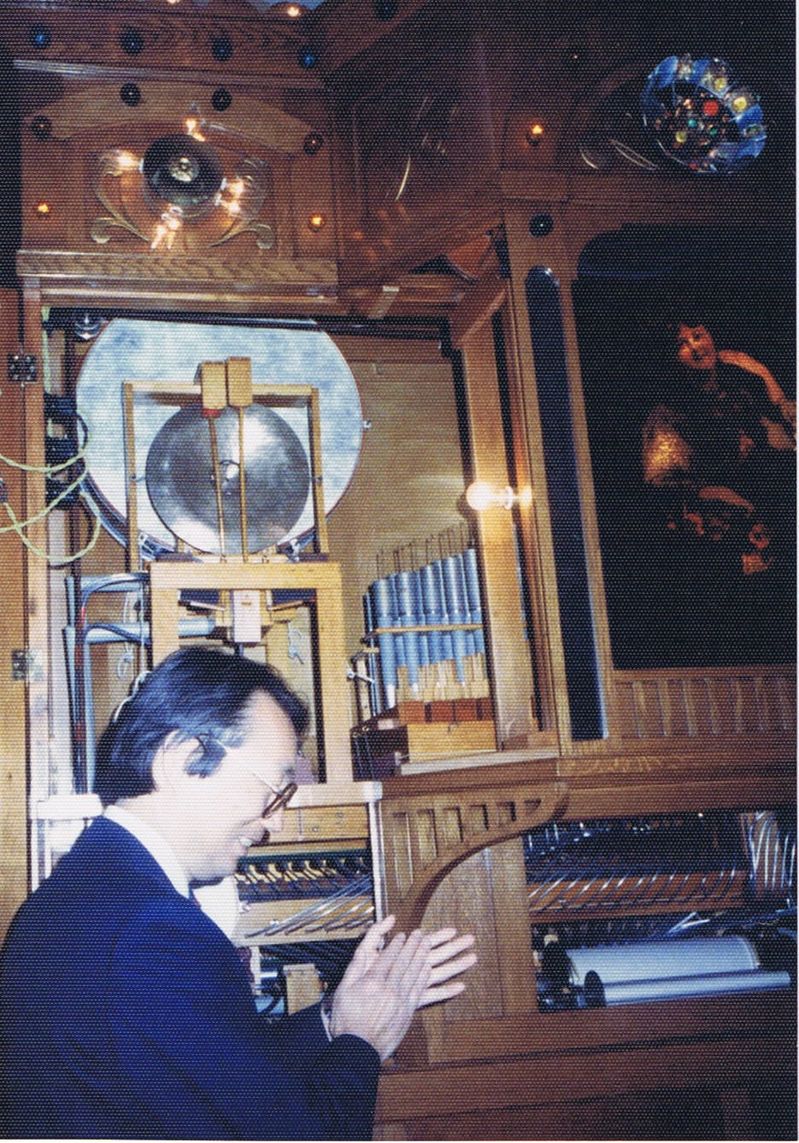

I have been to Kawaguchiko Music Forest Museum in Lake Kawaguchiko. They have a large collection of music boxes, including a Bechsteine-Welte, a player piano from Welte-Mignon, in the main hall. I asked them to play back Horowitz’s performance of Bach’s Prelude and Fugue, BWV 532 (roll number: 4127). He recorded it at the age of 23, and it was his only recording of this piece. According to the museum curator, Mr. Ishizawa, there are four kinds of player piano, and the one Horowitz played on was a top-end model called a reproducing piano. To be precise, player pianos and reproducing pianos are different. I brought with me an authorized reproduction of Horowitz’s piano roll that was made in the 1980s under a license granted by Welte-Mignon. I tried to mount the roll on their device but couldn’t because the paper width was a bit too wide and the hole locations were out of alignment. There are two kinds of piano roll from Welte-Mignon: ones for 88-key pianos (green rolls) and ones for 80-key pianos (red rolls). The photo below (from the handbook of TACET 138) is from when Horowitz had a recording session with Welte-Mignon.

Welte-Mignon at Kawaguchiko Music Forest Museum・piano and roll box

Red roll・green roll and Horowitz at recording

Mr. Ishizawa gave a detailed explanation about how they make a recording on a piano roll. When a pianist makes a recording, they play on a piano designed for such a recording. Several engineers from the player piano maker and other musicians usually attend the recording session. The engineers check the roll of paper on which the performance is recorded, and the musicians memorize the sound volume and other nuances while following the music score. This information is important for the subsequent perforation process. Why is this memorization necessary? Because the piano itself does not have a recording device, and the performance is carved on the paper set in the recording device at the side of the piano. However, the device merely places graphite marks on the paper. These marks reflect the volume to some extent but do not convey subtle nuances. So how do they attain verisimilitude? The paper roll for reproducing pianos has holes for indicating the volume and pedaling in addition to the pitch and rhythm, and they are handmade after the recording. That is why memorization is important. The craftsmen perforate the paper relying on the score and the musicians’ memory, and the paper roll undergoes repetitive trials. The end product is ready after six months to a year of refinement. Of course, the period varies according to the length of the piece and other factors. The pianist has to visit the manufacturer several times to see how the reproduction process is going. After fine-tuning the perforations to adjust the timing and volume, the pianist listens to his/her performance on the roll of paper, and upon confirmation that it is a genuine rendition, an autograph is added and the master roll is complete and becomes the basis for the mass production of commercial piano rolls. The photo of the recording session shows a technician standing in front of the recording device alongside the piano in an unnatural posture as if to hide the inside of the machine. Perhaps they needed to prevent their secrets from appearing in the photo.

The earliest effort in Japan to reproduce the piano rolls and re-release them in the LP format was made by Mr. Morita, a co-founder of Sony Corporation (CBS Sony The Great Pianists of the Century; Horowitz’s performance was in Vol. 5).

Horowitz at the recording session at Welte-Mignon (TACET138)

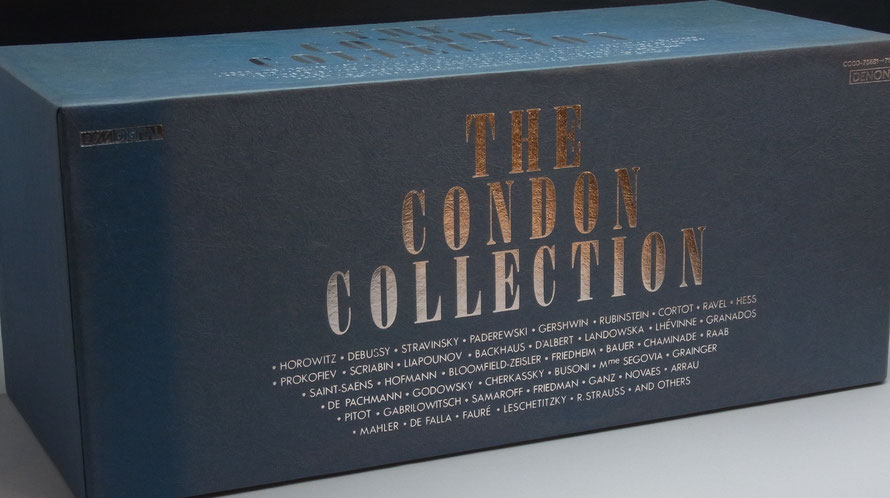

As far as I know, the most prominent piano roll collector is an Australian, Mr. Denis Condon. His piano rolls in the field of classical music have been reproduced as the “Condon Collection” on 32 CDs (COCO75681-712), the first of which contains Horowitz’s performance.

Condon Collection Box

Horowitz recorded three pieces twice for piano rolls. At first I thought it was a mistake when I found that the same piece had different numbers on LPs and CDs, but it actually denoted two different recordings. The three pieces are as follows:

(1) Bach/Busoni, Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C major, BWV564

WM 4121 (Adagio only), WM 4124 (Adagio and Fugue)

(2) Horowitz Variations on a theme from Bizet’s Carmen

WM 4120, DA

7250-4

(3) Schubert/Liszt Liebesbotschaft (No.1 from Schwangesang (Swan Song)), D 957

WM 4121, DA 7282-3

The following is a list of Horowitz’s piano rolls released as LPs. The number in parentheses is the number of pieces performed by Horowitz on the LP. For further information on what LP contains what piece, see Appendix II.1 “Discography of Piano Rolls” and Appendix III 18.9.

1. Welte-Legacy-Record (WLR), GCP-771B-14 (1)

2. CBS Sony, The Great Pianists of the Century, Vol. 5, 25AC245 (3)

3. The Keyboard Immortal Series, Vol. 6, Kbi 4-A068-S (4)

4. Intercord, INT160.864 (9)

5. Franz List Klavieraufnamen auf Welte-Mignon, EMI 067/EL 270448 1 (1)

6. Piano-Roll Collection, Vol. 5 GZ-7084 (1)

Note: The performances contained in Nos. 2, 3 and 5 above have not been released on CD. Also, I do not have No. 1, so its jacket image is not available.

LPs and open reel tape

The following is a list of Horowitz’s piano rolls that have been released as CDs. The number in parentheses is the number of pieces performed by Horowitz on the CD. For further information on what CD contains what piece, see Appendix II.1

“Discography of Piano Rolls” and Appendix III 1.

1. Victor, VDC-1313 (9), released in 1987

2. Intercord, 72435440232 (9), released in 1988

3. fone-90F12CD (5, including Cortot’s and Horowitz’s performances), released in 1990

4. DAL SEGNO, DSPRCD023 (12), released in 1992

5. DAL SEGNO, DSPRCD029 (1, Horowitz played Fantasy on Themes from Mozart's Figaro and Don Giovanni), other artists include Backhaus and Landowska, released in 1992

6. DAL SEGNO, DSPRCD038 (3, Horowitz played three Rachmaninoff’s preludes), other pieces include Scriabin and Prokofiev playing their own music, released in 1992

7. DAL SEGNO, DSPRCD035 (1, Horowitz played Tchaikovsky’s Dumka), released in 1992

8. DENON, The Condon Collection, No. 1, COCO75681 (12), released in 1992

9. Nimbus Records, The New Golden Era, NI8811 (6), the other performers are Chasins, Cherkassky and Goldsand and all come from Duo-Art’s piano rolls, released in 1997

10. Naxos, 8.110677 (1, variations on a theme from Bizet’s Carmen), other pianists include Paderewski, Cortot, Saint-Saëns, Hofmann and Gieseking, released in 2000

11. Victor, VICC-60184 (11), the other pianist is Cherkassky, released in 2000

12. J. Stewart Music, Masters of the Roll, Disc 1 (12), released in 2007

13. TACET, TACET 138 (12), released in 2008

14. TACET TACET 204 (3, the Rachmaninoff’s pieces (op. 23-5, 32-5, and 32-12) are from Welte-Mignon’s piano roll), and the CD also contains a performance by Josef Casimir Hofmann and many other pianists who were active until the 1920s, released in 2013

Images of 15 CDs

Some museums in Japan record the pieces on piano rolls by using reproducing pianos and then sell them as CDs. Some such CDs contain Horowitz’s performances.

Four CDs from museums in Japan

For further details of Horowitz’s piano rolls, see Appendix I.1 “Piano roll numbers and pieces performed by Horowitz,” Appendix II.1 “Discography of piano rolls” and Appendix III.1.

Column 2

Ampico and Nyiregyházi

I share a passion for collecting with Mr. Rick Crandall, the CEO of our partner software company and a good friend of mine. He was an enterprise software CEO and served as the president of ADAPSO, the computer software industry trade association in the early 1970s, when he was in his thirties. He is seen as one of the pioneers who started a software company at the dawn of the computer age. As a keen collector of cash registers and automatic music machines, he is world-renowned for cash registers and has published two books on them.

Cash Registers Book and Cash Register

Many of the music boxes Rick collected are now in Japan. They are displayed and played at various museums. The other day I went to Parthenon Tama in Tokyo to see some of his collectibles that are displayed there, and I also found a player piano made by the American Piano Company (abbr. Ampico). They let me listen to Rachmaninoff’s recording of his own prelude, op. 23-5. Rachmaninoff made his piano rolls only with Ampico, but Horowitz never played at Ampico. The photo below is an Ampico catalog published in 1925. The remarkable fact about these special pianos is that they are called “reproducing pianos” that play perforated music rolls originally recorded by the actual pianists including Rachmaninoff and Rubinstein themselves.

Ampico catalogs

According to the catalog, Ampico has a great number of piano rolls (not of recordings but the perforated paper rolls used to record performances). Among the performers who recorded with Ampico are Brailowsky, Copland, Dohnányi, Godowsky, Grofé, Kreisler, Lhévinne, Moiseiwitsch, Nyiregyházi, Rachmaninoff, Rosenthal, Rubinstein, Schnabel and Richard Strauss. We can now listen to Kreisler and the young Nyiregyházi play the piano. Nyiregyházi later became successful in a sensational revival in the 1970s and toured Japan. This was accomplished by having the original artist playing a piano that had small pens on the piano hammers and they inked marks on a blank paper roll, capturing the exact phrasing and expression of the original artist playing. When you listen to these rolls on the reproducing piano, you are hearing the original artist, not a recording.

Column 3

Horowitz plays Mozart’s “Marriage of Figaro”

When I was invited to Rick’s house, I saw an enormous 80-year-old music machine called an “orchestrion” sitting in his living room.

Rick’s Machine

He set a paper roll with holes into the device and let me listen to the Michigan University’s fight song. Orchestrions, which you can see at museums at tourist destinations, can be very big, as they can be stuffed with a piano, organ pipes, drums, and even real stringed instruments including violins and banjos. He said this orchestrion called “Felix” made by Popper, a German company, was rare and there were only three of them in the world. The paper roll was custom made; he ordered the roll with the tune specially arranged for his machine. The machine was so huge that he had to remove a wall to bring it in. The perforated music roll is the predecessor to computer software that is based on binary arithmetic of one’s (a hole is punched) and zero’s (no hole).

The basement, which was as large as a gym, was where he closely guarded his cash registers and the many music boxes and player pianos he collected.

Player Piano

Then he played the roll with Liszt/Buzoni’s Fantasy on Themes from Mozart's Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni, which Horowitz only recorded on piano roll. At that time, the recording was not available on LP or CD, so I had never listened to it before. I was deeply impressed with the experience and said I wished I could have recorded the sound. Then Rick, as if he could read my mind, gave me his roll with that piece. This became a genuine treasure for me, and now a recording of this piano roll is now available on CD.

Going back to the story of Rick’s music machine, I was curious about how he got this rare device. Collectors of music boxes are all very wealthy people, so no amount of money would tempt them into selling them. However, the previous owner was well known among collectors. So, one day, Rick visited the guy. First, Rick showed his collections to the previous owner, and then listened to the guy blow his own trumpet. Next, Rick casually brought up the music box and asked if he was interested in selling it. The owner flatly refused, of course. Then, Rick said, “What are you looking for now?” “A Nazi tank from World War II,” was the reply. “So, will you take a tank for that music box?” said Rick. The answer was “yes.” Then Rick searched for a Nazi tank all around the globe, and successfully bought one from a collector in Denmark. That’s why Rick got the much sought-after music box, which is now in the center of his living room.

The full story, with pictures, of this machine can be seen on the Internet at: http://www.rickcrandall.net/popper-orchestrion/ ). Also, Rick has written stories on many of his music-machines and their inventors which are on the Internet at: http://www.rickcrandall.net/music-machines/

To Chapter 3

ホロヴィッツの遺産

このサイトは20世紀最高のピアニスト「ウラジミール・ホロヴィッツ」に関するサイトである。

2014年11月5日 ホロヴィッツ没後25周年の命日に「ホロヴィッツの遺産」を出版した。本サイトはこの本の内容をアップデートするとともに、載せていない情報も掲載したサイトである。

このサイト・トップにある本は9,700円で販売されている。

本にはホロヴィッツが世界でリリースしたPiano-Roll,78回転盤、45回転盤、LP、CDのすべてがジャケット写真とともに掲載され、VHSテープ、LD,DVD等でリリースされた映像のジャケット写真のすべても掲載されている。

ジャケト写真は1,300枚に及び、コレクター必見の書籍である。

収集の際重複して集めたものは販売しております。

販売サイトはこちら。

ISHIIは1978年から日本で放送されたクラシック音楽番組を

個人的に録画してきた。これはDVD3000枚に及ぶ。

またISHIIはThe Hyper Print Art

と名付けた、新たな芸術分野を開拓したが、これらに関してはISHII and Daughtersをご覧頂きたい。

Mail address of horowitz.jp ishii@horowitz.jp