Chapter 1

1 The making of this book

What has made Horowitz my favorite pianist? This question had never occurred to me, but the co-author Jun Kinoshita prompted me to speculate about it by raising it while reading through my unfinished manuscript.

I am quite an intuitive person who judges everything, be it music, painting, art works or wine, by my feelings and preferences only. I do not care very much about public opinion. Fame and popularity might secretly affect my thinking, but my own judgment and impressions always come first. For example, wine is not about brands, unless the bottle is exquisite and very expensive; what matters most is my physical condition, and secondly with whom and in what restaurant I drink it.

Listening to Horowitz’s performance again, I reflected on what it is about Horowitz that fascinates me so much. First, his performance never tires me. Sometimes I feel I have had enough while listening to a piece of music, but I never think this way when it comes to his performance and Wagner’s works. There is something intoxicating about his piano playing, which makes me addicted. Once you fall in love with him, you will find other pianists boring. You will admire someone like him, too. For example, Arcadi Volodos. I cannot work while listening to music—I always want to concentrate on the music. Then, I feel drawn into Horowitz’s world; or rather my anticipation grows larger while listening.

Second, his piano sounds are truly fascinating. Quite distinct from others. Some people believe his piano has special contrivances, which is not true. His tonal uniqueness largely comes from his playing style. But he must have chosen instruments that would make his favorite sounds and Steinway took special care of his pianos and appointed Franz Mohr as his exclusive tuner. Therefore, his “special” pianos would have played a part.

What is the secret of his tonal variety and transparency? Any dillydallying is alien to his music—and the contrast of lyrical expressiveness and strained outburst at top speed is overwhelming. No other pianist can produce his magnificent dignity.

His playing order is also excellent. He never played etudes in serial order unthinkingly. Maybe not to tire the audience, or rather, himself.

My favorite renditions by Horowitz regarding composers are as follows: Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, Chopin, Scarlatti, Schumann and Debussy. I don’t like his Beethoven performances. I don’t think Horowitz liked Beethoven very much. He recorded Beethoven’s works often when he did not give public recitals, so the recordings were probably requested by recording companies. His Bach and Mozart are not bad. However, in his 1965 comeback recital after 12 years of absence from public performances, he starts the first piece of Bach at a terrific speed, and then gradually calms down in a charming, smile-inducing way. His Mozart performances in later years are also exquisite. However, with Scriabin’s Vers la flamme (Toward the Flame) and Sonata No. 10, Rachmaninoff’s prelude Op. 23-5 and Sonata No. 2, Liszt’s Sonata in B minor and Vallée d’Obermann (Obermann’s Valley), and Balakirev’s Islamey: Fantaisie orientale (Oriental Fantasy), he rose to a great artistic height that other pianists would never be able to reach. These renditions simply show he is the best pianist ever.

The following details how I “met” Horowitz and began to collect his recordings.

1.1 1950s and 1960s—craving for classical music

In 1950, as a sixth grader I listened to an orchestral performance for the first time ever, which was conducted by Hidemaro Konoye in Shibuya Public Hall, which was in a different location to where it is now, and whose stage had tatami (rice straw mats) in front of it. This was a musical entertainment for grade-schoolers, where they first played Leichte Kavallerie (Light Cavalry) by Franz von Suppé, introduced musical instruments and their sounds to us, and performed Ravel’s Boléro. I still remember how moving the music was.

At a school festival at Aoyama Gakuin Junior High School, the Fire Department Band appeared on stage. I had a big smile when I listened to them at the front, and as I found I was unable to straighten my face after the performance, I pressed my cheeks down with my hands. There was a pipe organ in the Charles Oscar Miller Memorial Chapel of Aoyama Gakuin, where we had services several times a year, and I was also fascinated by the colors of the organ sounds.

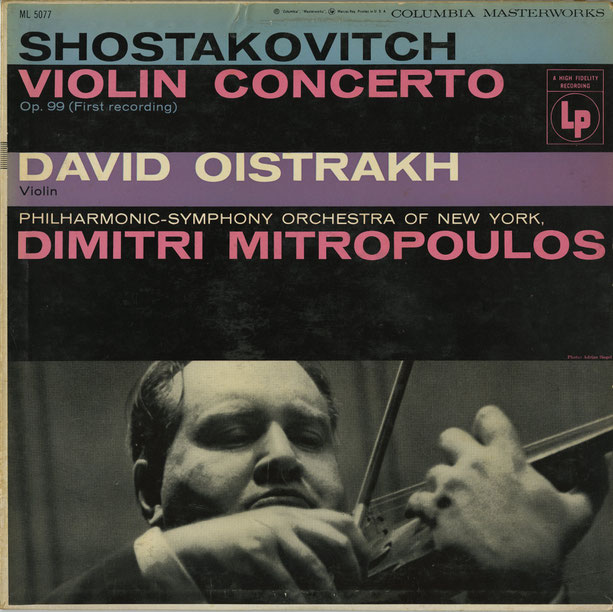

I proceeded to Aoyama Gakuin High School and became a hard-core classical music lover. One of my best friends, Tatsuya Takizawa, had played the violin from an early age and I frequented his house, where we often listened to classical music. He is a son of a church minister, and they had a fancy audio system that his brother made, with which we would often enjoy LPs and 45s loudly that had only recently come onto the market. And since his house was actually a church, it had an organ, on which his brother always practiced some piece or other by Bach and Buxtehude as well as hymns for worship. That is why they had a vast collection of LPs from Archiv Produktion. His father liked classical music and had a great number of 78s. On top of all these, we devoured the 45s and LPs of violin pieces that occupied the house because Takizawa played the violin. My favorite was Dmitri Shostakovich's violin concerto No. 1 by Oistrakh.

This piece was actually dedicated to Oistrakh and no doubt it was fantastic. The LP was worn out so they ended up buying another. We also listened to numerous violin and orchestral pieces, and relished János Starker’s cello over and over again.

Takizawa usually practiced the violin in the church. One day we put on an LP of Kodaly’s Cello Sonata by Starker and someone dropped in because he believed someone was actually performing this supreme music in the church, as they were always practicing music in the church.

After 1950, leading musicians from around the world visited Japan one after another. Violinists such as Heifetz, Oistrakh and Kogan, pianists like Cortot, Gieseking and Backhaus, top-tier orchestras led by Karajan, Stokowski, Bernstein and Munch, composers including Stravinsky, Copland and Messiaen, and Lirica Italiana (Italian opera companies invited by NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation)). Takizawa skipped school and stood in line from early in the morning to get a ticket for Heifetz, Oistrakh and Kogan. I vividly remember glued to the radio.

From the mid-1950s to mid-1960s, NHK radio 1 and 2 aired my favorite weekly show called Rittai Ongakudō (Stereo Music Hall) for two radio sets. We happened to have two radio sets, so I positioned these two radios side by side. By the combination of these two, I could enjoy stereo.

Well into the television era, the last few concerts of Lirica Italiana in Japan culminated with Giordano’s Andrea Chénier by Mario Del Monaco and Renata Tebaldi. It was a landmark performance in the history of classical music in Japan. I was a student and could not afford a full ticket; I witnessed just one stage at the hall, but I watched a full version on TV, which led me to make a lifelong commitment to classical music.

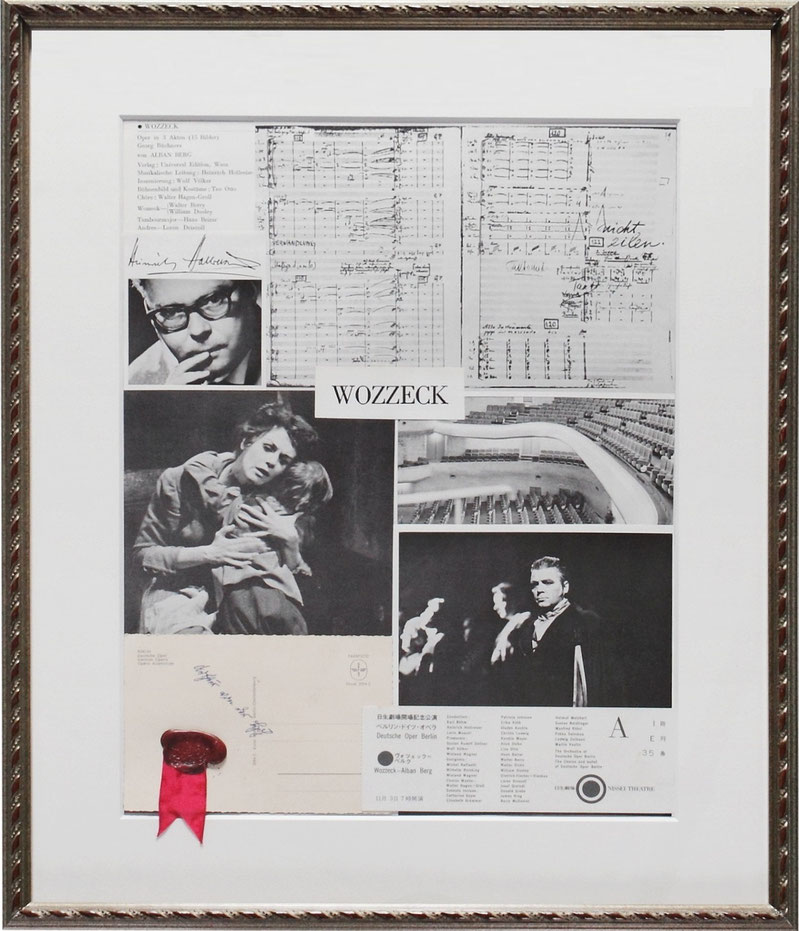

In 1963, Nissei Theater opened as Deutsche Oper Berlin performed Fidelio, The Magic Flute, The Flying Dutchman and Wozzeck. Karl Böhm and Lorin Maazel were among the conductors. I witnessed Wozzeck (Japan premiere) in the theater and watched The Flying Dutchman on black & white television. Josef Greindl performed the role of the Dutchman. They said he looked like a real ghost on TV because the stage was very dark for dramatic impact and the TV cameras of the day did not represent the stage well. I still remember how marvelously Ballade der Senta (Sente’s Ballad) was sung. The TV program certainly made me a Wagnerian.

The framed ticket for Wozzeck is an example of the frames in which I arranged the photos of impressive scenes, conductors and performers from a concert program as well as the ticket to honor the memory of the performance. In this way, I can enjoy the experience twice, first by enjoying the music and second by making and displaying these frames.

Around the time NHK started FM broadcasting, they aired classical music programs day and night, and I opened my ears to wider ranges. At the end of December every year, NHK broadcast all the performances of the Bayreuth Festival that year, which gave me immense pleasure. Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) was also broadcast almost every year. Since Wagner was my favorite, I was quite excited about it.

In 1963, Lirica Italiana held a charity concert in Osaka. I still remember the unforgettable songs of Ella giammai m’amò by Nicola Rossi-Lemeni and Una furtiva lagrima by Ferruccio Tagliavini. All the singers sung wearing a medal awarded by the Empress, who was the Honorary President of the Japanese Red Cross Society.

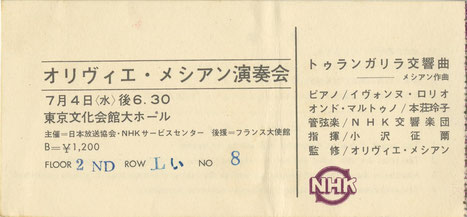

I was impressed with Leopold Stokowski, who conducted the Japan Philharmonic in 1965 and conducted Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4. Also, Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring conducted by Igor Markevitch and Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique (Fantastical Symphony) directed by Charles Munch were also stunning. I thought the Japan Philharmonic at that time was at an extraordinarily high level, perhaps because my friend Takizawa belonged to them. It is also unforgettable that Rudolf Serkin performed Beethoven Piano Concertos No. 3 and No. 5 in one evening, In 1962, Seiji Ozawa directed Turangalîla Symphonie with NHK Symphony Orchestra (Japan premiere) in the presence of the composer Olivier Messiaen, which showed me the splendor of modern music. Messiaen appeared on stage after the performance and admired how quickly Ozawa had grasped the music.

Turangalîla Symphonie (ticket )

This performance was soon broadcast on radio, which I recorded with a tape recorder in my house and listened to again and again. However, shortly after Ozawa was rejected by the orchestra members of NHK Symphony Orchestra and its regular concerts were cancelled. I remember a telegram was delivered to my house to inform me of the cancellation. NHK regular concerts were cancelled several times due to the incident. They resumed in 1963 with the conductor Hiroyuki Iwaki, whose first appearance with Beethoven’s Leonora Overture No. 3 was amazing. I suppose the members of the Orchestra simply did not like Ozawa, who had graduated from Toho Gakuen School of Music, because most of them were from Tokyo University of the Arts. At any rate, the performance was so vigorous that I have to say the alumni of Tokyo University of the Arts were indeed distinguished.

In 1967, the Bayreuth Festival Opera came on tour to Japan and appeared at the Osaka International Music Festival, with gorgeous singers such as Birgit Nilsson and Wolfgang Windgassen.

1.2 1970s—encounter with Horowitz

I had not particularly favored piano performances and Mozart’s pieces. Then, what made me so obsessed with Horowitz?

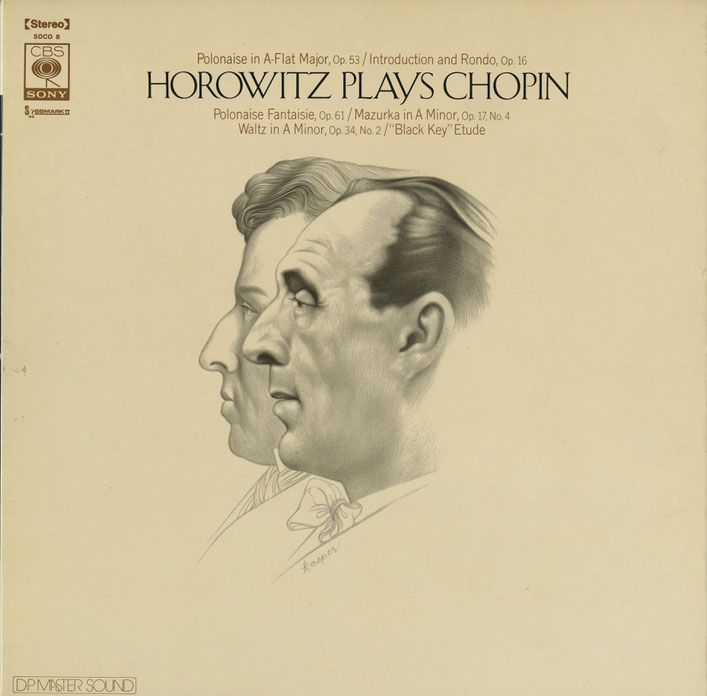

Around 1972, my eldest daughter, who was then an elementary student, practiced the piano. I still did not like piano music, so one day I asked her, “Can you ask your teacher which pianist plays great?” The teacher’s choice was Rubinstein or Horowitz’s Chopin. I heard Rubinstein play a piano concerto wonderfully in Philadelphia in 1968, so I thought I should go to see him, but then I also remembered about talking with my boss when I arrived in the USA in 1967. Asked what my favorite pastime was, I replied classical music. And then he said, “Everyone in New York is talking about Horowitz. What do you think?” When I replied I knew nothing about him, he gave me a look of derision as if to say that I was just a clunk. I had little interest in piano performances, so I didn’t even know the name of Horowitz.

In 1971, Takizawa invited me to his house so we could Horowitz’s performance on NHK together. Gee, that dude was a sensation in New York. I went to Takizawa’s house and saw him play on TV—that famous Horowitz on TV filmed by CBS. Wow, fabulous. It was the first time in my life that the piano had fascinated me.

These two preludes led me to pursue Horowitz, not Rubenstein. I soon visited a record shop in Shibuya to buy an LP of Horowitz playing Chopin, accompanied by my daughter whose teacher had recommended that we buy it.

LP of Horowitz playing Chopin

On returning home, I listened to it and found it heavenly. The next day, I went to the shop again and bought another one from the same craftsman. Well, awesome. So I bought all the Horowitz LPs in the shop. I listened to one after another. They were all great. Never had I had such an experience before; it pulled me into the amazing world of his playing.

Hoping to find more, I looked in another record shop. I found one or two new LPs, though most of the ones they had were the same. I listened to them and found them magnificent, too. I went to another and yet another shop, but I couldn’t find any new ones. That was an end to my treasure hunting, but soon, a new LP was released by CBS Records. I wasted no time in getting and listening to it. Marvelous. When was the next one coming out? I couldn’t wait any longer. I kept searching shops for other existing LPs but they had nothing to offer. One day I found an advertisement of his other LPs in some information material attached to an LP. Since I didn’t have them, I hurried to a record shop but with no luck. They should have been on the market but were not available. I tried another shop in vain. Then Mr. Yamamoto, my senior office associate who loves classical music, suggested I check secondhand record shops in Kanda Jimbocho and Ochanomizu in Tokyo. I was excited to find more of his LPs there and bought everything. Asked why I had to buy so many LPs by my daughter, I made up an excuse, “I’m buying these LPs now to run a record shop after retirement.” She seemed convinced, surprisingly; I knew that she wanted to criticize me for buying a large quantity of LPs at one time when she could hardly afford to buy just one LP. Anyway, I was now publicly allowed to make a bulk purchase of Horowitz’s recordings. I became semi-serious about my tale of purchasing merchandise for my future business.

At that time 78s were no longer on sale, but some shops in Kanda Jimbocho still had some secondhand ones, which I also began to collect. Of course, my collection was limited to Horowitz. The shop sent me their sale list every few months, and I got almost all of Horowitz’s. I also bought a turntable, an arm, and a cartridge for 78s. My audio set included a Western Electric amplifier made in 1933 and VITAVOX speakers for theater use. The Western Electric amplifier 46B had an output transformer that had been used in movie theaters in America. Massive and heavy, this system is still in use at my house.

Western Electric Amplifier 46B

The 78 format, which had been widespread before WWII, was gradually replaced by LPs and 45s from around 1950 and almost disappeared in the 1960s, but we have no choice but to obtain 78s to listen to some of Horowitz’s performances as they are only available in the 78 format. However, many of his 78s were lost during the war and I couldn’t find any rare ones.

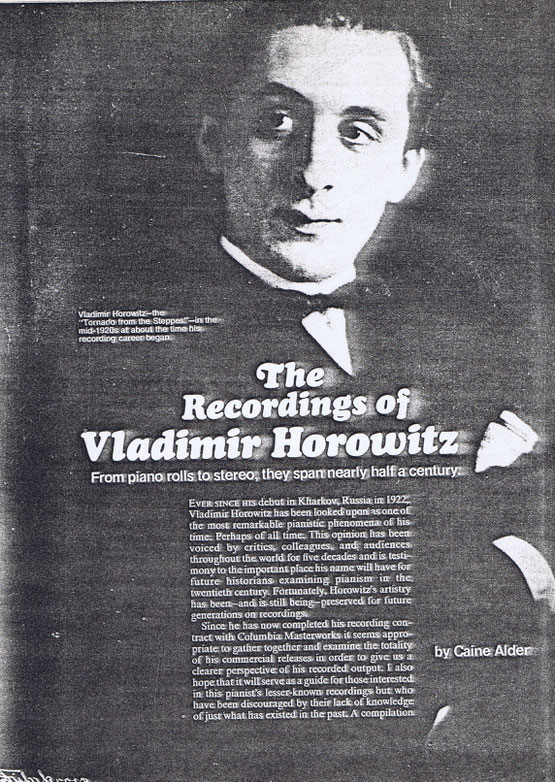

It was in 1973 that Caine Alder published the first, nearly complete discography of Horowitz in the July issue of High Fidelity.

The Recordings of Vladimir Horowitz by Cain Alder in 1973

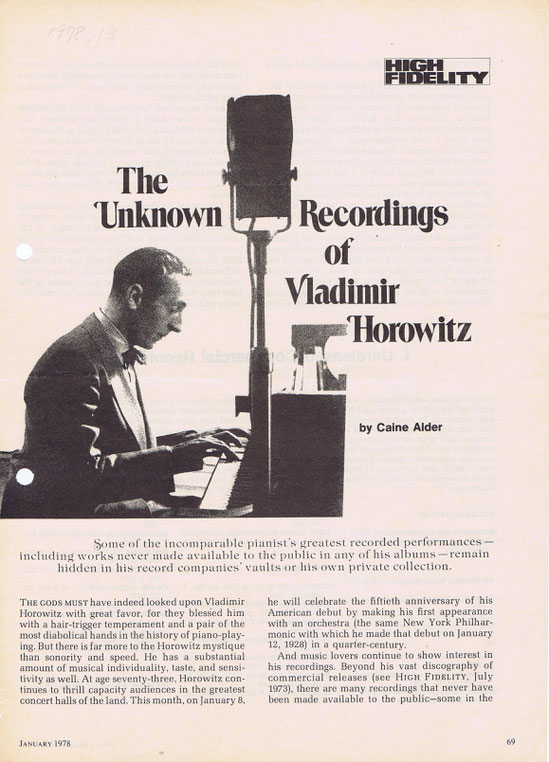

I didn’t know about the article at that time, but Mr. Yamamoto told me about another article written by Alder in the 1978 January issue of High Fidelity, in which he referred to the discography.

The Unknown Recordings of Vladimir Horowitz by Cain Alder in 1978

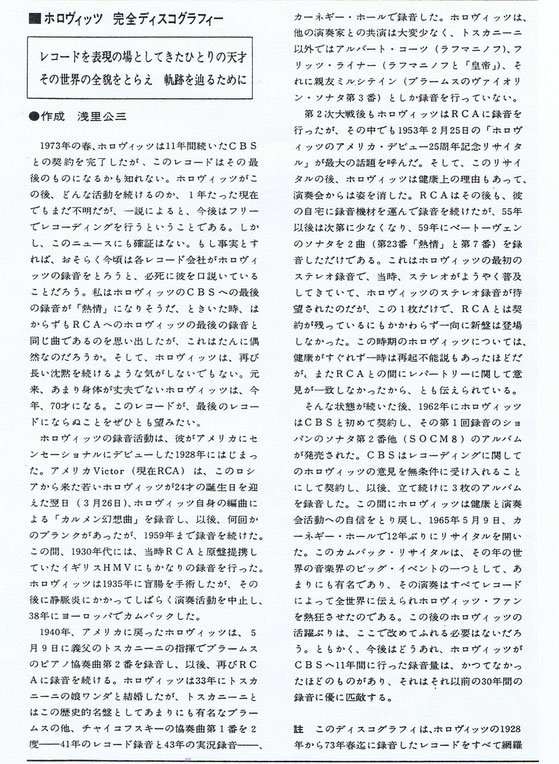

Probably drawing upon Alder’s discography, Kozo Asari was the first Japanese to produce a Horowitz discography in Japan. This came out in the liner note of Horowitz’s LP that was released by CBS Sony in 1974 (SOCO72), and he added that the list included several recordings whose existence was not verified, including Flight of the Bumble-bee by Rimsky-Korsakov and The Russian Dance from Petrushka.

Complete discography of Horowitz by Kozo Asari in 1974

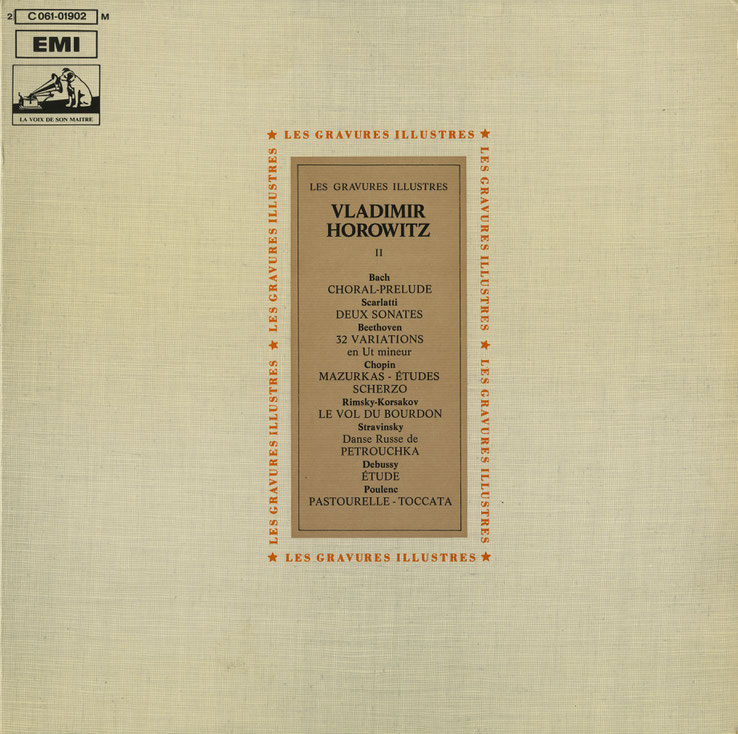

I visited the National Diet Library in Tokyo and obtained a copy of the 1973 January issue of High Fidelity, in which Alder said that both renditions were released by HMV in the 78 format and their reprinted versions were available on an LP from a French label, Pathé.

My job included frequent visits to foreign countries, and I looked around used record shops all around the world, from London to Paris, Frankfurt, Milan, Wien, Los Angeles and San Francisco. And finally, I found the Pathé LP in New York.

Pathé LP

Of course I was thrilled. But these days we can get hold of these one-time rare recordings on CD. Furthermore, what I used to search every corner of the world for is now available for free on the Internet. This was a personal downer as I felt like my invaluable treasure was instantly taken away from me.

Be that as it may, each time I was in a foreign city on a business trip, I looked up the local telephone directory and advertisements in the journals of classical music to make a list of secondhand record shops, and marked them on a map. Then I took a taxi to the neighborhood where those shops were located and visited them. One day in San Francisco, I hired a taxi and made a pilgrimage to several record shops. Then, the driver asked me if I was interested in some good secondhand record shops in Barkley, a neighboring town on the opposite side of San Francisco Bay. I had only checked the San Francisco phone directory, and my list did not include Barkley shops. So we went there and found several used record shops dedicated to classical music. The driver asked me what I was looking for. I said Horowitz, and he offered to help in my hunt. We got along well and had a great day. He gave me his business card, and we parted with a promise to make a tour again next time I was in San Francisco.

In London, near Waterloo Station, there was and still is a secondhand record shop specializing in classical music called Gramex. They posted an advertisement almost every month in a British classical music magazine. So I went there but they were always closed. The entrance was on the ground floor but the store was upstairs. I did see the store name in small letters at the entrance; I visited three or four times over several years but they were always closed. One day, I finally found it open. I entered the shop and found a shopkeeper.

“Why aren’t you open every day?” I asked.

“We are open every day,” he said.

“Well, I’ve come here many times but you were always closed.”

“What time did you come, sir?”

“Nine thirty or ten in the morning.”

“Oh, we open at 1 p.m. every day.”

I complained I had wasted my time because they did not put their opening hours at the entrance, but the damage was done. I told him I was looking for Horowitz LPs and asked him where I could find them. His answer was that all the records were placed randomly so I would have to search every shelf myself. I had no choice but to frisk the room—my wife and a working companion also joined me. Luckily a ladder was there, and I got some rare recordings released in the UK. I was such an eager beaver that I always visited shops in the morning, but in vain.

In this way, my record shop list became more and more complete. Now I had the opening days and hours of all the shops for future convenience, and continued my search whenever I had time. I also created my own ranking of such shops. This list became an important basis for building my Horowitz collection. I still have this list for each city in my passport case.

1.3 The Year 1978—a trip to New York to listen to Horowitz

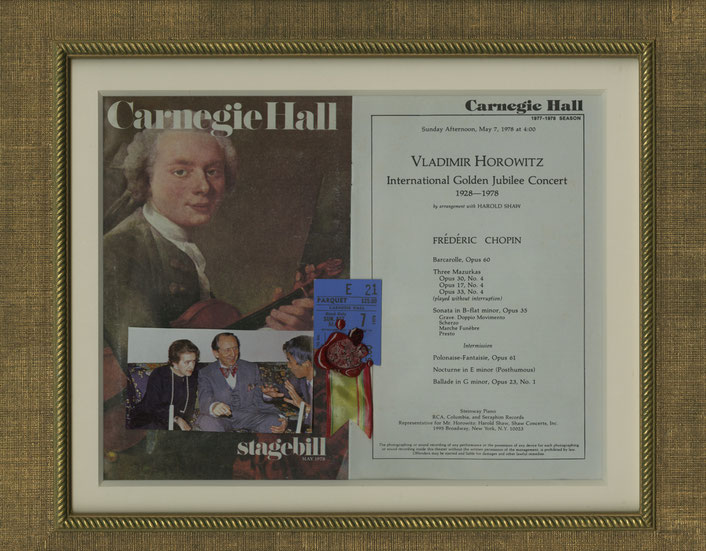

The year 1978 saw the 50th anniversary of Horowitz’s American debut. Someone told me that Horowitz would give a recital Horowitz International Golden Jubliee Concert: 1928–1978 in Carnegie Hall mainly for non-US residents. Well, it was time to go.

I found a tour operator in Kyobashi, Tokyo had organized tickets and would conduct a tour. I applied for it. An exclusive tour for Horowitz fans sounded like great fun, but my schedule did not allow me to go with them. I took another flight, and soon a Japanese woman sitting next to me started some paperwork. She was turning over the pages of some appointment book, which included the names of some orchestras including the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra and concert halls. I couldn’t help peeking. Convinced that she was a musician, I asked her, “Excuse me, are you a musician or a music industry person?”

“Yes.”

“Actually I’m a big fan of Horowitz and on the way to New York to listen to him.”

“Oh, me too.”

Now we got hyped up. The woman was a pianist, Ms. Akiko Sugitani.

The recital was held on May 7, on Sunday, at 4 p.m. It was an all-Chopin program. My seat was E-21 in the fifth row. An announcement was made, which told us that taking photos or recording was not allowed. It was given in English, French, German, Italian and Japanese because the audience was from all around the globe.

The program and ticket for the 1978 recital

Horowitz started playing Chopin’s Barcarolle, but I did not take in the sound very well. It was as if the sound went far above my head. Maybe I was too nervous with breathless attention at my first live Horowitz experience.

Anyway, time passed so quickly, and it was time for a break. There were also chairs on the stage surrounding the piano and many enthusiasts went up to sit there. During the break, they went up to the piano and started examining it. Soon, several came through the wings up to the stage and began to stare at Horowitz’s piano. Though hesitating for a moment, I automatically proceeded to the stage and gazed at the piano. Now I feel so embarrassed by that graceless act. About 40 to 50 people were on the stage. A member of staff dashed over and urged us to move away. Franz Mohr, an exclusive tuner for Horowitz, described in his book how a number of tuners came from Japan to attend the concert, and some of them went up to the stage and took photos. This outrageous act was also pointed out in the prefatory note by Takeo Murata, Witness to the Horowitz recital in New York in the July 1978 issue of the Japanese music magazine Record Geijutsu. I truly regret our mischievous behavior. The piano was a gift from Steinway when Horowitz married Wanda Toscanini.

Next to me sat a Japanese guy who lived in New York and identified himself as Mr. Mochizuki. He said, “I live in New York because I love Horowitz. This seat was originally assigned to the pianist Hiroko Nakamura, but we swapped places because mine was better.”

The tickets got into only a few American hands, while about 200 Horowitz fans came from France and Germany, and 140 from Japan. The audience also comprised British, Italian, Brazilian, Lebanese and many others. I could not find Ms. Sugitani, who had melted away into the huge crowd, but after several years I went to her recital in Tokyo.

One or two years after the legendary New York concert I remember that the travel agent informed me of another Horowitz concert in California. I jumped at the opportunity, but the concert was canceled. I could not believe my ears and called the agent again and again to see if it was truly canceled. Unfortunately, they flatly confirmed that was the case.

Around this time, Daimaru department store near Tokyo Station periodically held secondhand record fairs. As I worked in Yaesu, near Tokyo Station, I often browsed there during my lunch break. One day, I found a heap of Horowitz LPs the covers of which I had never seen. Out of the blue, what I had been looking for, for so many years were right in front of my eyes. More than that, some of them were priced at an outrageous 38,000 yen! Even the cheapest of the ones that were missing from my collection cost 16,000 yen. I hesitated over buying them because they were way too expensive. Maybe they were overpriced because Daimaru only dealt in rare items. But no other LPs were more than 10,000 yen; only Horowitz’s LPs.

Off the top of my head I thought: are there any other collectors of Horowitz’s LPs like me? Is there anyone willing to buy one at 38,000 yen? So I just took all the Horowitz LPs in the fair and placed them together in one corner. I paid a daily visit to see if they had been sold. Not today. Not the next day. On the last day, I went there just before closing. After all that, no LPs at 38,000 yen had been sold.

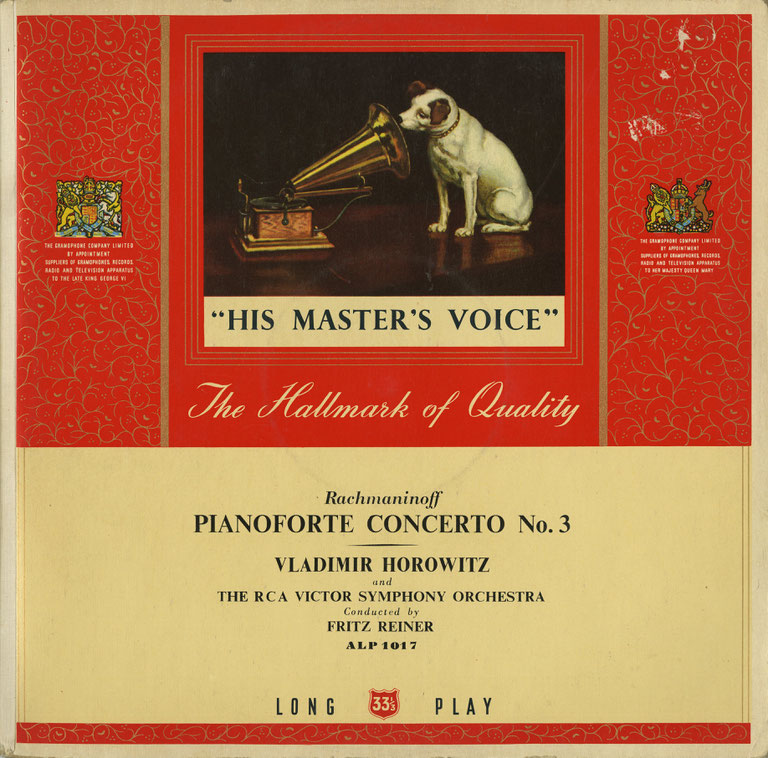

I learned several lessons. First of all, Horowitz’s LPs sold at a higher price than others. Secondly, the LP with a red jacket and a dog logo print that was priced at 38,000 yen was obviously an especially-hard-to-find item. There were still a lot more of Horowitz LPs that I needed to complete my collection. In evaluating their rarity, the pricing at Daimaru would be a useful benchmark. This experience drove me to collect Horowitz’s records even more, as now I knew clearly the ones I did not have. I felt that I would probably be able to find the French-made LP if I could find the LP with the dog logo in London. The Daimaru fair gave me a lot of clues, and it was overseas that I later got all the LPs that I had seen there.

LP “His Master’s Voice”

1.4 The year 1983: Horowitz in Japan

I continued my search for Horowitz’s records whenever I went abroad. Then, in May 1983, I heard such tantalizing news: Horowitz was coming to Japan! I was filled with joyful expectations and decided to stand in line in front of Kajimoto Music Office (now Kajimoto) at Ginza all night long, just like many fans had queued up and spent the night outside for a ticket to the legendary 1965 Carnegie Hall concert. I really enjoyed the experience of waiting in the street to get a ticket for Horowitz’s concert, but actually, a friend of mine kindly stood in line most of the time and I spent only a little while there. The long queue was covered by the TV news, as was the recital when it was broadcast on NHK. I went on screen with Mr. Kazuhiko Seto, and also with Mr. Jun Minagawa with whom I made the list of Horowitz’s repertoire. The list has been continuously updated, and the latest version is included as Appendix V. Those who were at the beginning of the line in front of Kajimoto Music Office stayed in touch with each other, and I joined the Horowitz Fan Club, which was inaugurated by Ms. Kyoko Kato.

Flyer Horowitz Fan Club written oath and photo of flower

Over the following two or three years, they held three or four meetings, but then we regrettably lost contact.

Be that as it may, I got tickets for two nights featuring the same program. The ticket price for S section seats was 50,000 yen, which was higher than those for an opera tour to Japan. I could hardly believe my ears at the recital on the first night. It was a total disappointment and I could not get over it for several months. The performance was broadcast on TV the next day, and a music critic Hidekazu Yoshida dubbed him a “cracked antique.” How I wish Horowitz had not come to Japan! My treasure was not a “cracked antique.” But I feared that even my friends might be thinking that I was foolish to pay 50,000 yen for a single ticket, only to see junk. No way! In fact, his performance on the second night was much better—I wanted to cry out, but his reputation rapidly diminished in Japan after that. The Steinway piano CD75, which was played by Horowitz then, is now owned by Takagi Klavier in Japan. On June 19, 2012, I listened to a Japanese pianist Akira Eguchi play on this instrument.

Flyer “CD75” Piano Recital Program

Had his abilities dwindled due to age? I remember Cortot also showed some signs of senility when he came to Japan ages ago, though much milder than Horowitz. Well, perhaps we should accept the reality of life, but it was a bitter pill to swallow. In the meanwhile, my collection kept growing.

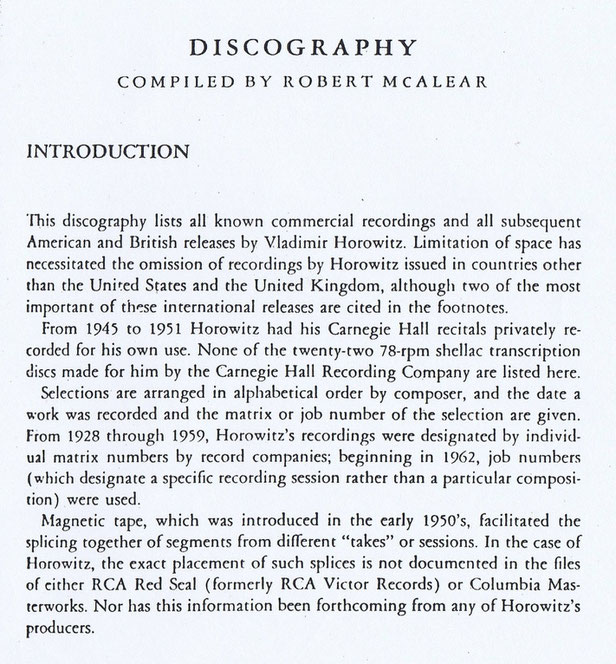

In 1983, Glen Plaskin published Horowitz: A Biography of Vladimir Horowitz.

Books of Glen Plaskin

It was the first serious biography of Horowitz, full of anecdotes heretofore unknown, and included a discography compiled by Bob McLear that was more complete than previous ones. For me personally, it was a crucial resource that further fomented my collection of Horowitz’s work.

The first page of the discography compiled by Robert McLear

I continued to explore this discography and prepared a list of record numbers that I did not have at that time. Initially I went around the globe chasing some of these acquisitions, but eventually reached the point where I could no longer find anything new in any shops. I did not want to experience disappointment when I visited a record shop with high expectations only to return empty-handed. So I began to buy what I already had as long as they were rare. My collection of LPs, 45s and 78s steadily expanded to approximately 2,000 items.

Comparing some of the records I had thought to be the same, I found slight differences such as the position of the logo mark or the inclusion of a program note. I also found many records that had the same record number but different jackets, or that had the same jacket but different record numbers.

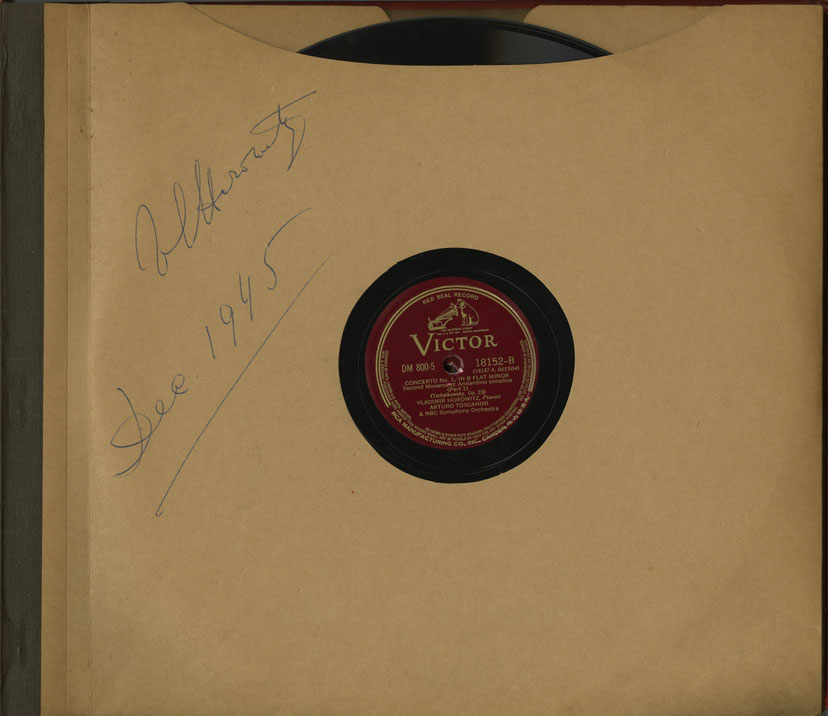

I obtained a 78 from RCA and a 45 from HMV. I came across many 78s in London, Paris and Hollywood. One time, I unexpectedly found a 78 that had Horowitz’s autograph on the paper bag. It is now one of my most precious treasures.

78 with Horowitz’s autograph

In Paris, I always found it difficult to locate local record shops, but one day I asked a friend, a college professor, to take me to some shops. He contacted one of these shops and found an individual who owned a large number of Horowitz’s 78s. During my stay in Paris, he took me to the collector’s house. The person was not a dedicated collector of Horowitz, but he did have many 78s. I bought a lot but had a hard time bringing them back to Japan because they were heavy and fragile. I had to take them with me into the aircraft as carry-on baggage.

1.5 1986—Horowitz Comes Back

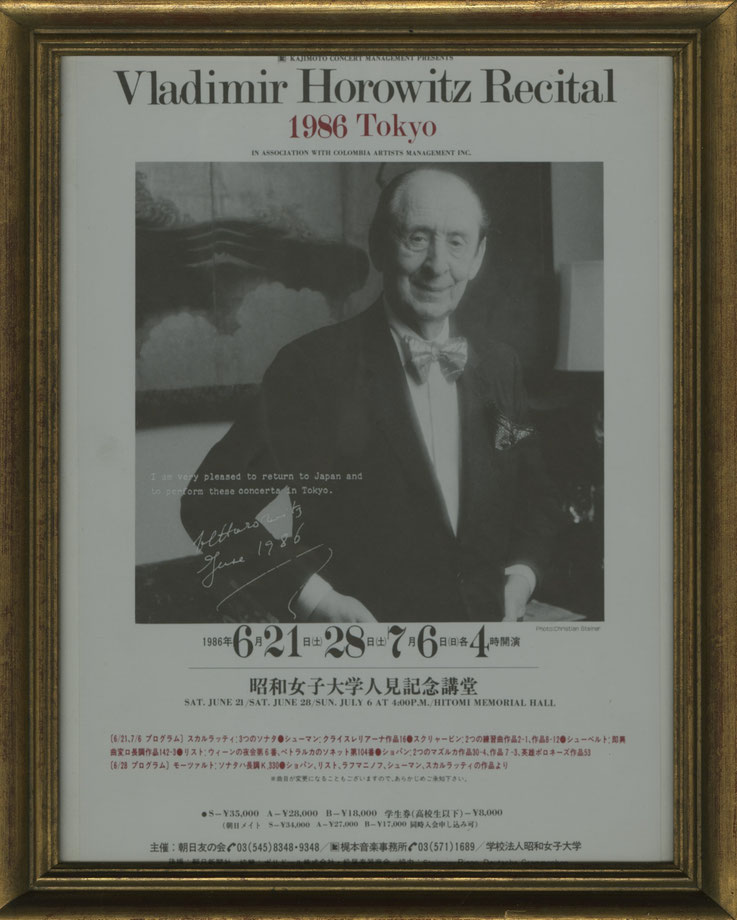

I had completely gotten over the nightmare of 1983 when I heard that Horowitz was coming to Japan again in 1986. What a surprise, but rejoicing at the thought of listening to Horowitz’s performance once more, I found myself in line in front of the Kajimoto Musical Management office again. The air of excitement was not as palpable as before, but the number of people in line was almost unchanged.

1986 Recital Flyer

This time, Hiroshi Saito kindly stood in line for me, so I spent only few hours in the line. Unfortunately, I could not attend all three of the recitals due to my business trip, but managed to attend the last one. I sat in the front row with my wife, 10-year-old youngest daughter, and friends from the Horowitz fan circle. The instant he stepped on the stage again, we realized that Horowitz was fully revitalized and refreshed. On the same evening, the second recital was being aired by NHK-FM. After the concert, I went straight home and listened to the radio together with my family and my fellow Horowitz fans. My friends had already listened to the recitals live, so we spent the evening chatting all sorts about Horowitz, his music and live piano performance. We enjoyed the night and were delighted at his successful recitals and recovery.

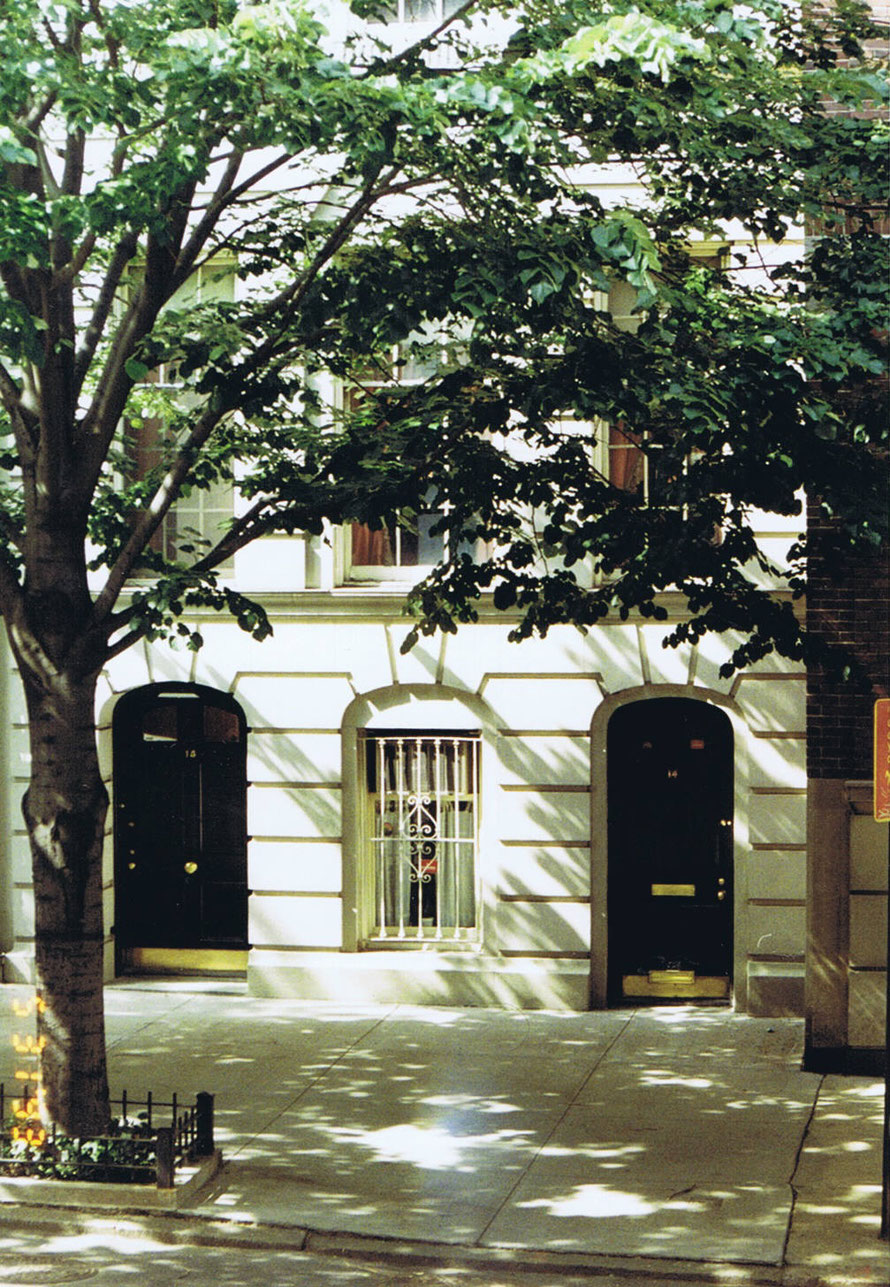

Around this time, his new recording became available both on LP and CD, and I also started collecting CDs. When I went to New York City, I took a taxi from the airport to the hotel, and as always, drove past Horowitz’s house on 14 East 94th Street.

Horowitz’s Residence

I always asked the driver to make a brief stop and to then continue on our way to the hotel. Unfortunately, I never saw the maestro getting out of his house, but I would simply have backed off and watched him passing by had he done so, as I didn’t have the nerve to run up to him to ask for his autograph.

There were a lot of secondhand record shops in New York, but they closed down or moved to another place more often than those in other cities. Some shops even dealt in secret recordings of various music, including Horowitz. Of course, they did not put a sign that said, “Secret tapes available.” The shopkeeper somehow spotted what their customers were looking for, and discreetly asked, “Would you be interested in this?” On one occasion, I answered yes, and he said it was $95, adding that the product was out of stock and he would later send it to my home address. I decided to trust him. He only accepted cash, and of course, did not provide a receipt. Fortunately, the tape was sent to my house in Japan several weeks later.

Tapes

The recording quality was not too bad. After that I visited the shop several times more and bought various tapes of Horowitz. When he recognized me as his loyal customer, he let me see a list of secret tapes of Horowitz. He also stored numerous unofficial recording lists of many other famous performers. I asked him to provide a copy of the Horowitz list, but he flatly refused. I shared this story with Hiroshi Saito, who lived in the US around that time, and he went all the way to the shop a few days later and copied it by hand. Now I had a much clearer picture of the concert performances of Horowitz that had been recorded, officially or unofficially. This further fueled my collectomania.

When making pilgrimages to used record shops, I sometimes dug up rare products. There seemed to be private associations that distributed what Horowitz fans or theater engineers had secretly recorded to their members in the LP format. They were supposed to have been for members only (as they came with a tag saying “Not for Sale”), but came on the market for some reason. Their jackets were white or plain in color, and some of them had no text. On the other hand, the LPs that the Bruno Walter Association and the Arturo Toscanini Association distributed to their members have printed texts on the jackets. These include Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with Bruno Walter and Toscanini, and Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with Bruno Walter, George Szell and Serge Koussevitzky. Most of them were later released as formal LPs in Italy, and are now available as CD as well. Both kinds of recording will be detailed in the following.

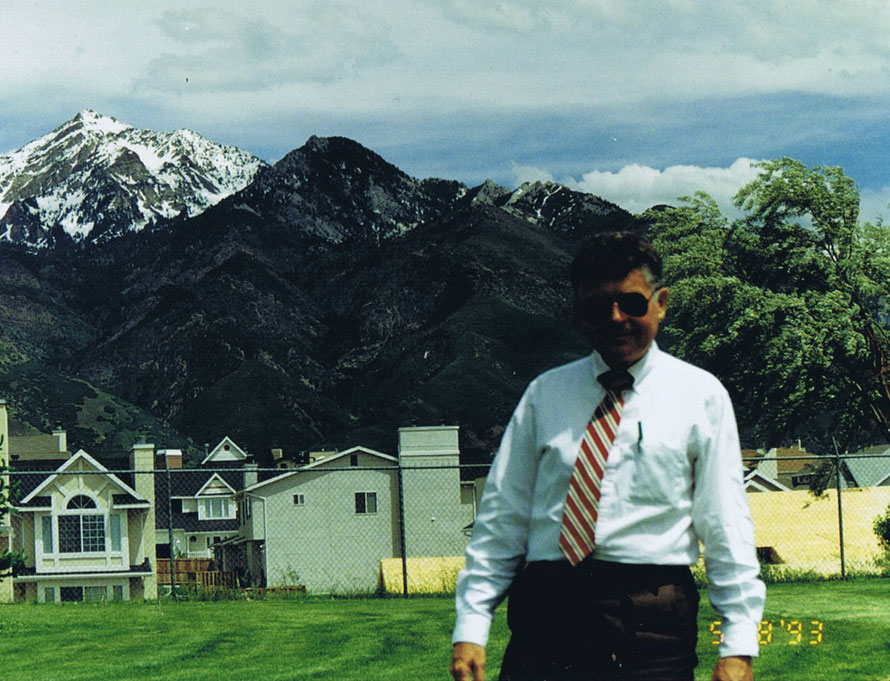

The best expert and collector of Horowitz in the world is probably Caine Alder, who published the first complete discography of Horowitz in 1973 as I said earlier. I desperately wanted to meet him, and visited his house in Salt Lake City, Utah in 1987. His house was commonly known as Horowitziana, and I found a Steinway grand piano in the living room. He was familiar with the Horowitz family, and Horowitz trusted him completely. As I showed him our imperfect repertoire listing, he wasted no time in correcting it and adding further information with a red pen, without any reference source. For seven or eight hours, he let me watch Horowitz on TV (a 1968 recital) and listen to various recordings from the Yale Collection as well as many others that I did not know at all. The Yale Collection is a series of recordings that Horowitz himself asked Carnegie Hall to make of his 15 recitals including encores, and it is so called because the collection was later donated to Yale University. Not a single piece I listened to in his house was published at that time.

Everything Alder shared with me was so fascinating that I could not leave even after the sun had set. His wife showed up and talked in whisper, and they kindly invited me to dinner. I joined the table with them and their daughter. He even gave me a videotape of Horowitz on TV when I left his home.

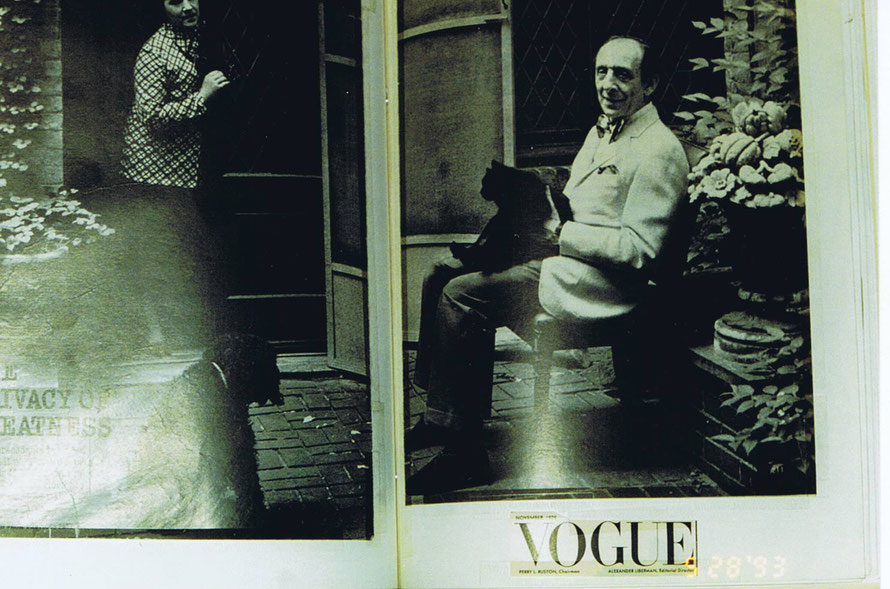

Alder told me that he first became enchanted by Horowitz because his father was a great devotee of Horowitz. This meant he had adored Horowitz for more than 70 years. He had neatly organized old newspaper and magazine articles that he had gathered over a long period. I took a photo of some of them, which is reproduced below.

C. Alder’s scrapbook

Here one question arises: Alder had a copy of the Yale Collection and let me listen to some of them, but why did he have them? It was because he had said to Horowitz, “We should hold a copy as a backup in case the original is damaged or lost. I will not give it to anyone, so please let me make a copy.” Horowitz initially said no, but his wife Wanda Horowitz agreed to this idea and persuaded her husband to let Alder have a spare. On top of this collection, Alder had 150 concert tapes, most of radio broadcasts, and what recording companies had recorded but not released. He seems to have written the article on High Fidelity in 1978 based on them.

A Letter from Cain Alder

By the way, when I was in Israel on business some time earlier, I took a taxi to pay a visit to Rubinstein’s grave, located on the top of a hill near Jerusalem. The gravestone was huge, and it reminded me of piano keyboards. I took some photos of his tombstone, and I decided to give them to Alder as a small gift.

Rubinstein’s tombstone near Jerusalem

1.6 1989—Horowitz’s Death

On November 5, 1989, Horowitz died of a coronary at home, just a few days after his home recording session with Sony Classical. My heart sank but I knew it was inevitable given his advanced age. The news made headlines around the globe, and my friends abroad sent me numerous newspaper and magazine articles about his death.

Articles from New York Times and Italy

I collected all the articles and recorded all the TV news in Japan. I also edited a video recording and distributed it to other Horowitz fans.

Mr. and Mrs. Horowitz wanted to be buried in the Toscanini family tomb in Milan because they wanted to join their daughter Sonia who had passed away after a motorcycle accident. That is why Horowitz’s funeral was held there. Probably at Wanda’s request, his funeral service took place in La Scala, where the funeral of her father Arturo Toscanini had also been held. Upon seeing this news, I contacted a friend in Milan and went to the Monumental Cemetery in 1990. The administrative office in front of the entrance of the Cemetery kindly helped me find the Toscanini family tomb. I brought some flowers and laid them in front of the gravestone. The tomb was five meters tall with an iron door in front. I decorated the door with the flowers. Someone had already put flowers into the door, so I decided not to take them away but to place mine around them. Horowitz’s name had not been inscribed but I guessed his body was placed on the third shelf on the right side from the top, as he had requested that he be buried next to Sonia.

Horowitz’s grave

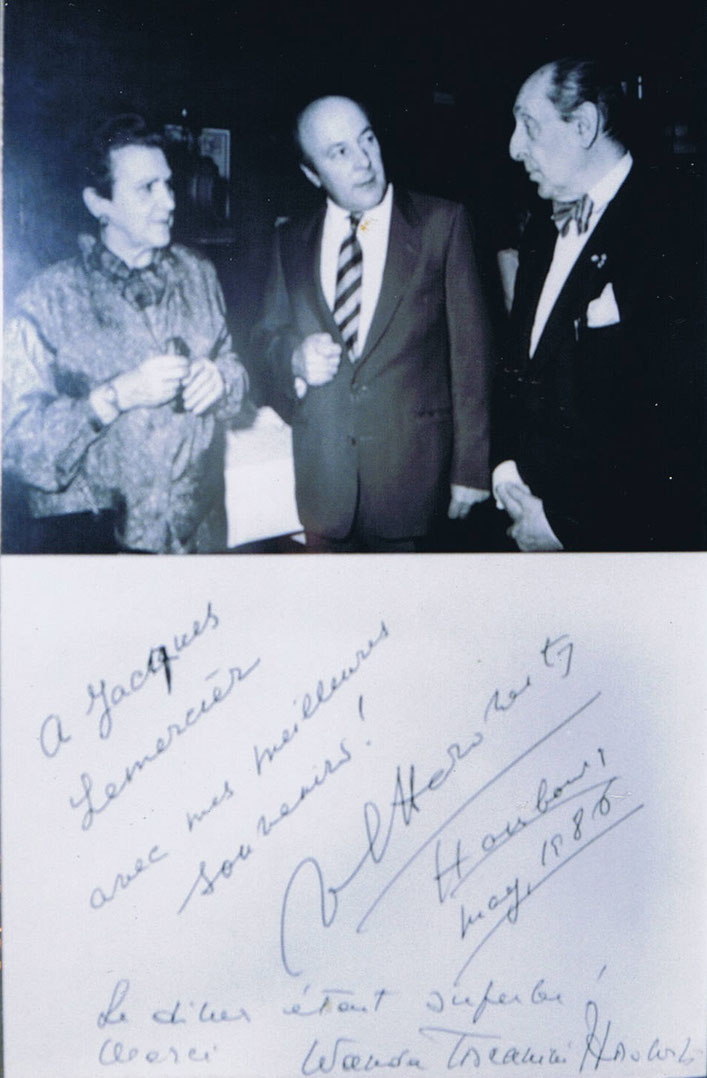

On another occasion, I visited Hamburg on business. My fellow Horowitz aficionado Hiroshi Saito, who had visited there to attend Horowitz’s recital in 1987, had heard from a Japanese violist at Hamburg State Opera about a restaurant where Horowitz had had dinner. I asked Saito in Japan to contact the violist, and we had dinner together there. We enjoyed seeing Horowitz’s photo and autograph on the wall of the dining hall, and so we sat just next to them and ordered the same dishes as Horowitz.

Photo of Mr. and Mrs. Horowitz at the restaurant

Since 1986, Jun Kinoshita, the co-author of this book, has been involved in our collection activities. He has detailed knowledge about Horowitz’s LPs and CDs and kindly helped me identify the ones I didn’t yet have. From 1997, he also informed me of rare Horowitz recordings that were being sold on Internet auctions. He bought new CDs on overseas websites and bid for rare LPs and CDs at auctions for me, thus helping me add several hundred LPs and CDs to my collection. Another item of booty at such auctions was a photo of Horowitz with Toscanini and Bruno Walter. He surely knows much more about Horowitz than I do, and has helped me grow my Horowitz collection to be evermore comprehensive; my current collection would not exist without his tremendous contributions.

Photo of Toscanini, Horowitz and Walter

One day, Kinoshita brought a small magazine ad for a bronze statue of Horowitz’s hands playing the piano. The gallery was just to the north of the former World Trade Center in New York, and I lost no time going there. The bronze statue was made by Dr. Stanley Taub an artist who was also a professional plastic surgeon and ran the gallery. He was selling other bronze statues of Rubinstein and a ballet dancer which was probably modeled by his wife (a professional ballet dancer). I was not very impressed by the large bronze statue imitating Horowitz; it looked like just an ordinary old man and was unappealing in my eyes, though it was quite an accurate look-alike. However, I liked the bronze sculpture of his hands very much, so I purchased it and added to my collection.

Bronze statue of Horowitz’s two hands

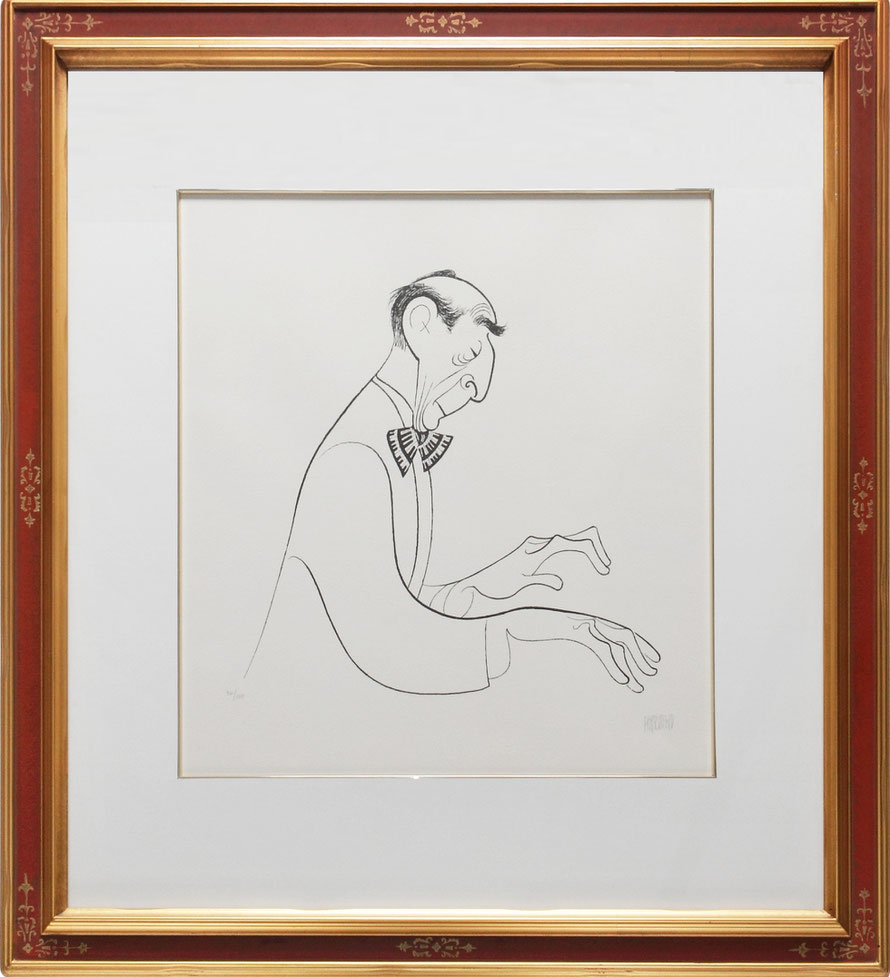

On another occasion, I happened to watch a TV program that showed a gallery in New York, where a large collection of Hirschfeld’s works was displayed. He was known for drawing portraits of musicians, including Luciano Pavarotti and Leonard Bernstein. In the program, I heard a store clerk mention that they also had his portrait of Horowitz in stock. I wrote down the name of the gallery so that I could visit it the next time I was in New York. We did not have the Internet at that time, so I asked the hotel concierge there to locate its address and buy the drawing.

Horowitz’s Portrait by Hirschfeld

1.7 1990s―Disclosing Horowitz’s Repertoire

After Horowitz passed away, I still continued collecting his LPs and CDs enthusiastically with the help of Jun Kinoshita, an increasing proportion of my collection now being CDs. The last recording session in 1989 was released on LP, cassette tape, DAT and CD, but the LP version was not released in Japan. Horowitz’s recordings were archived in all the formats available in the history of music recording, from piano roll to CD. As detailed in the following, a piano roll was one of the earliest media, along with Edison’s phonograph using wax cylinders, that allowed us to record and reproduce musical performances.

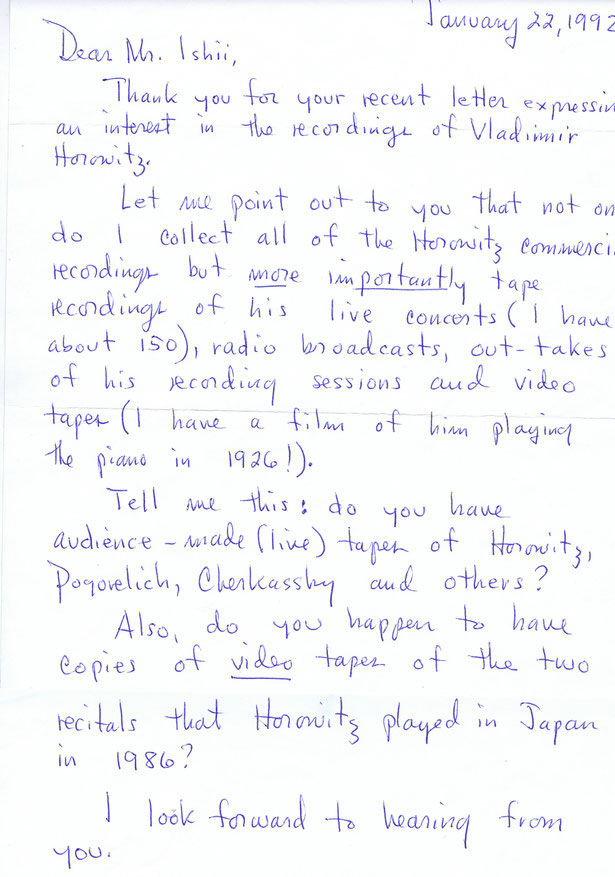

In 1993, I met Cain Alder again in Salt Lake City. He lived there because he liked mountain climbing. I gave him a photo of Horowitz’s tomb in Milan. We exchanged letters about 10 times in total, and when I sent our discography to him in 2011, he kindly reviewed and corrected it.

Mr.Cain Alder

I sent him recital videos of Vladimir Ashkenazy, Shura Cherkassky and Ivo Pogorelić at his request. In exchange, he sent me the recording of the 25th anniversary recital of Horowitz’s American debut in 1953 on CD. He said that the official version had been partially modified, and the CD he had sent me was of the genuine original performance, including all encore pieces.

In 2011, he sent me an e-mail saying in excitement that he was keenly interested in an amazing young pianist Yuja Wang, and asked me to send him some recordings. I sent him a DVD-R on which I had recorded her recital that had been broadcast by a Japanese TV station, but due to an issue with regional differences he could not run it on his US DVD player, and I had to ask him to buy an all-regions player. In 2012, his wife told me that he had departed this life. I deeply mourn his passing.

In the field of visual recording, Horowitz first appeared in a silent movie in 1928 (or 1926). Alder had a copy. Subsequent video recordings of Horowitz include:

Horowitz on TV (1968)

The 50th anniversary concert for America debut (1978)

Horowitz at the White House hosted by President Jimmy Carter (1978)

Horowitz in London, a charity concert hosted by Prince Charles (1982)

Horowitz in Tokyo (1983)

The Last Romantic, a home recording session (1985)

Horowitz in Moscow (1986)

Horowitz plays Mozart, a studio recording of a Mozart piano concerto in Milan (1987)

Horowitz in Vienna (1987)

Most of them can now be found on YouTube, but at that time I had to ask my friends in the US and the UK to send me the TV recordings of his recitals. Of course, I tried to record all the TV programs broadcast in Japan.

After Alder passed away, we started to complete Horowitz’s repertoire list. What to include in the repertoire was a tricky issue. Should a piece that Horowitz recorded only once at the request of a recording company be included? Would he call a piece of music that he does not like a repertoire piece? However, as it was impossible to ask Horowitz in person, we decided to include in the repertoire the pieces he formally recorded and/or played in a public performance. We have no idea how Horowitz felt, but we adopted the “formality” criterion anyway. Alder had advised us to specify his favorite pieces chronologically. I agreed with this but it would require more investigation. Therefore, we focused on giving the big picture first and then making a chronological analysis.

Kazuhiko Seto produced a repertoire list through a comprehensive investigation of documentation, while I investigated numerous discographies and liner notes. Jun Minagawa reviewed the accuracy of the music titles and created a database. Titles that appeared on LPs, CDs or 78s were often incomplete and we often had to verify the recording with the score. Seto and Minagawa took on this laborious task. Finally, we completed Horowitz’s repertoire listing “Rev. 1.1” on October 1997.

During 1999 to 2000, to mark the 10th anniversary of Horowitz’s death, numerous CD collections were released. We can now enjoy all the piano rolls on CD, including Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro (Le Nozze di Figaro) that I had listened to in my friend’s house, and all the remastered 78s that had been sold by HMV and RCA were rereleased on CD, except one piece that Horowitz did not allow to be published. Also, new recordings continued to be released, and a part of the Yale Collection also became available on CD. We therefore revised the repertoire listing several times to arrive at “Rev 1.4.”

One day in 2002, Kinoshita told me via e-mail that a young northern European man called Christian Johansson had launched an amazing website on Horowitz. It was indeed staggering, detailing when, where and what Horowitz played, as well as what recording was available. Though not entirely free from mistakes, it was definitely a first-rate information source on Horowitz. I found some discrepancies between our data and his, and began exchanging e-mails with him. We sent our repertoire list to him and pointed out his errors. He politely gave us a reply and corrected his errors. On the other hand, we found numerous mistakes in our repertoire listing while investigating his research so that we were able to revise ours significantly (“Rev. 1.8”). We further updated the list several times as Horowitz’s unreleased performances were put out on CD. The latest version (“Rev. 4”) can be found in Appendix V.

1.8 Subsequent Events

Around 2010, Jun Minagawa created a sound database that archived all the available CDs and private recordings owned by Horowitz fans in Japan. Thanks to this, I now listen to his music by connecting my PC via a DA convertor to a stereo preamplifier and a Western Electric amplifier.

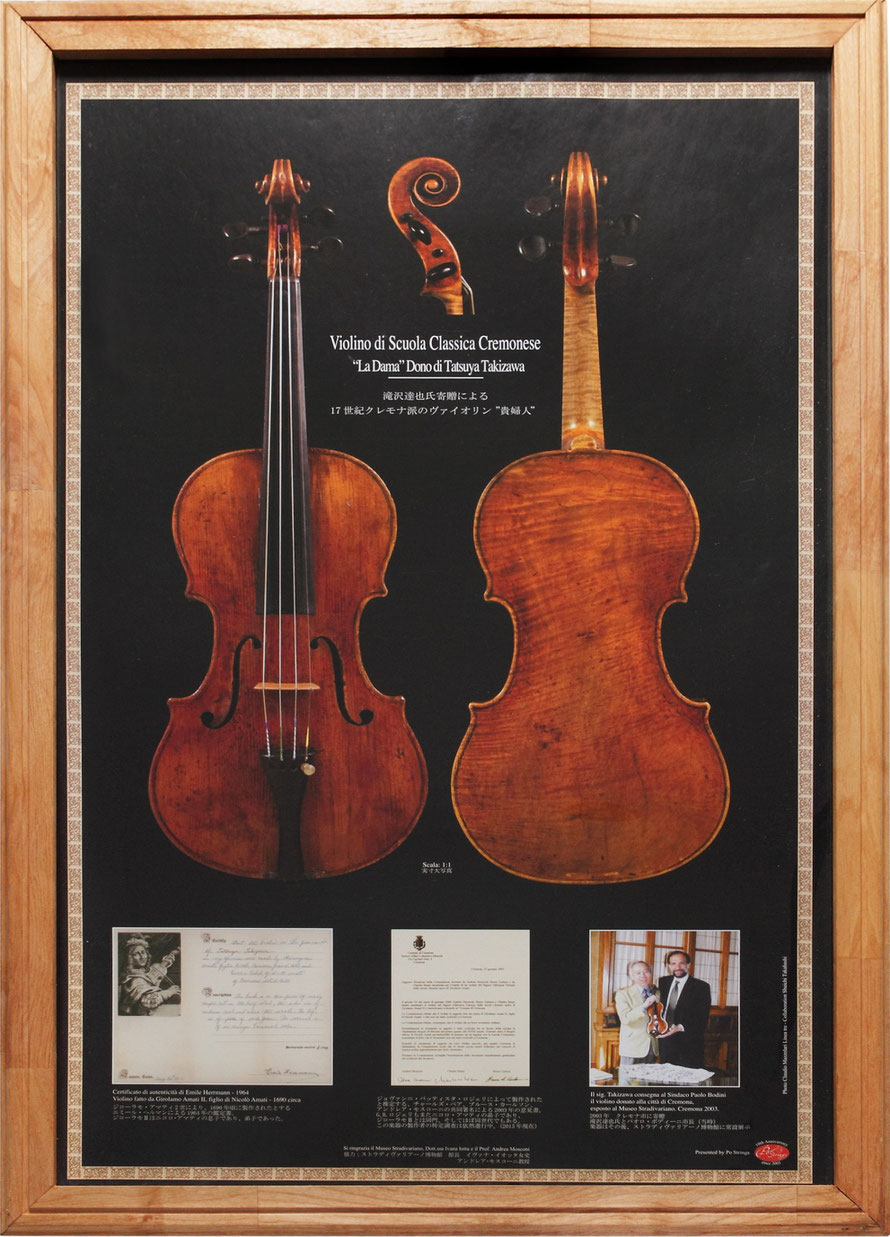

Let me now talk a little about my best friend Takizawa, who introduced me to the splendor of classical music. In 2003, he donated his violin (probably an Amati) to Cremona City in Italy, which is now in the custody of the Stradivarius Museum. It was in a petite size for female violinists, so he called it “La Dama.” He purchased it from a member of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1964 during their Japan tour. He later found out that it was one of the instruments that a musical instrument dealer had bought from Jewish people at cheap prices during the Nazi regime. The instrument was known to exist but no one knew its whereabouts until Takizawa obtained it.

After 300 years, the veneer on the face of the violin had become irreparable. Takizawa discussed the problem with a professional restorer and tried to do all he could do, but to no avail. He came to the conclusion that its life had come to an end, and decided to return it to its birthplace, Cremona. The research by the museum later revealed that it was indeed an instrument that was produced in Cremona around 300 years ago, but they are still investigating whether it is an Amati or not. Takizawa passed away in December 2012 before he knew the final result of the analysis. I deeply mourn over his death.

Photo of Takizawa’s Amati

I should also mention that I went to see a theater play titled Dialogue with Horowitz at the Parco Theater in Tokyo in February 2013. It was a special event produced and directed by Koki Mitani for the 40th anniversary of the theater. The protagonist was a professional piano tuner Franz Mohr, and I found the scenario amusing particularly because it included some conversations between Wanda and Mohr’s wife Elizabeth about child-rearing as well as some between Mohr and Horowitz. Mohr was played by Ken Watanabe and Horowitz by Yasunori Danta. Both were leading Japanese actors, and it was such a commercial success that tickets were difficult to obtain. The program note says that the play was based on Franz Mohr’s book My Life with the Great Pianists as well as D. Dubal’s Evening with Horowitz, G. Plaskin’s Horowitz, P. Brunell’s Vladimir Horowitz: le Méphisto du piano, H. Schonberg’s Horowitz: His Life and Music and Shigemi Takajo’s Steinway Story. Although it was fictional, it was free from unreal exaggeration and I found it quite enjoyable. Of course, Horowitz did not play piano during the play. We did hear live music played by a pianist, but none of Horowitz’s recordings. How Horowitz was selfish was amusingly described, and the fact that his daughter Sonia had already died was skillfully incorporated into the scenario.

Dialogue with Horowitz

In May 2013, I visited a record shop in Hollywood for the first time in 18 years. The shop had relocated to a new address but was still run by the same owner. I had bought a lot from the store in the past, and they never changed their way of selling goods without price tags. They watched the customers and decided on the prices. The same shop assistant was working there, tight-lipped and gloomy, and looking geeky. Just as he had done so 30 years ago, he deftly helped me find Horowitz’s recordings on the various shelfs while murmuring something. He was responsible for the record inventory. When an LP was sold, he would fill the space with another LP of his choice. He would also return the records he had pulled out that the customers did not buy. This would be why he knew the exact location of each recording. The record shop was larger than before, and had a lot of jazz LPs in addition to classical ones. A lot of record collectors from all over the world pay a visit to this shop.

A while ago, Yuri Temirkanov, a Russian conductor at Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, dropped into the shop and spent two hours searching for rare items. A photo of him on that occasion decorates the wall of the shop. Actually, he is my friend: in 2001, I invited him and the orchestra to Japan, and they gave three performances in Tokyo and Yokohama to celebrate the 25th anniversary of my company. One of the concerts was broadcast on NHK BS. When I told the story to the shop assistant, he looked at me in disbelief.

Concert Program of St. Petersburg Phil with Y. Temirkanov

When I visited the store 18 years ago, the shop assistant showed me a photo collection of Louis Armstrong that he made himself, saying that a Japanese might be familiar with Akira Tsumura who was actually the president of Tsumura & Co. On the first page was Tsumura’s photo, and the collection was an exquisite discography with a lot of LP jackets inside.

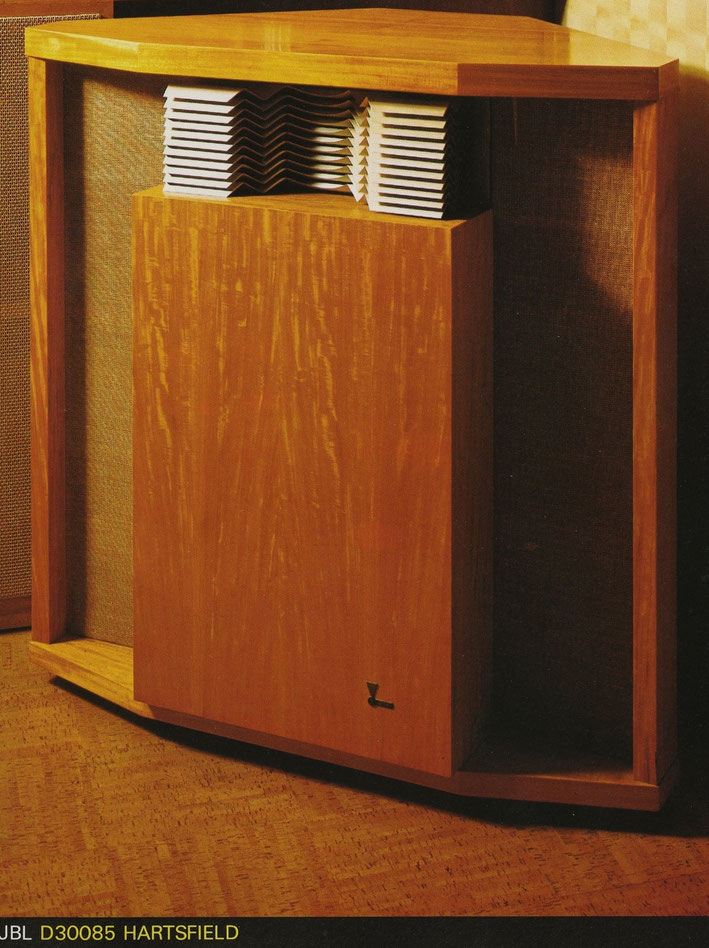

Since then, the shop had expanded its floor space, and they now had many vintage audio players that included masterpieces such as the Paragon and Hartsfield made by JBL and a prototype of the Patrician 800 by Electro-Voice. The Patrician 800 has two boxes on one side, so a stereo system would require four. They also had an Autograph by Tannoy and a Klipschorn by Vitavox. All these were world-leading masterpieces that I listened to admiringly in a showroom in an audio shop at Akihabara, Tokyo when I was younger. This time I bought several 45s and LPs of Horowitz. Out of them, only one 45 was a new addition to my collection.

Hartsfield by JBL

In August 2013, Sony Classical released a CD box of Horowitz’s live performances at Carnegie Hall. This collection includes numerous never-before-published performances, and what is important is that all the concerts including encores were packed into the CDs without being edited. Compared with previously released CDs, we can feel the ambience of the concerts more vividly. On one occasion (November 24, 1968), an accident happened—while he was playing Rachmaninov Piano Sonata No. 2, a piano wire snapped. This collection includes this performance unrevised.

Horowitz on TV was also released by Sony Classical. It was based on two concerts on January 2 and February 1, 1968, and the video had only been available underground and was actually a splicing patchwork of the two sources. The Sony version includes the two complete sessions separately on CDs, and we are very pleased that it is now formally available. Compared with the informal version I had, some scenes are different, and the visual quality is improved.

Johansson’s website (the Horowitz website) shows that there are still many unreleased sound sources. I hope that more and more of Horowitz’s unreleased recordings will see the light as 30th anniversary of his death is approaching. We also have many unofficial recording collections that have not been officially released, so there are probably plenty more unknown recordings around the world.

Column 1

Tatsuya Takizawa Donated an “Amati”

My friend and a professional violist Tatsuya Takizawa donated his favorite violin that was probably produced by Amati to Cremona City on October 1, 2003, and the instrument is now held and exhibited by the Stradivarius Museum. This instrument had a checkered destiny and finally reached its haven.

Takizawa bought this violin from Peter Hermann, a member of the Berlin Philharmonic when the orchestra gave concerts in Japan in 1964. Hermann’s uncle, Emil Hermann, was a leading instrument dealer of the day who collected numerous masterpieces. He also bought many great instruments from Jewish people who were usually persecuted during World War II at unjustifiable prices. After the war, this act gave him a bad name, and Hermann’s store in New York went bankrupt. The masterpieces he had collected were scattered and lost around the world. However, this violin remained in his hands because its back was damaged and needed major repairs. According to Hermann’s appraisal, it was produced by Girolamo II Amati, a son of Nicolo Amati.

This was a petite violin, and believing that it was cherished by a young lady, Takizawa named it “La Dama” (the lady) and used it regularly. However, the veneer of this 300-year-old instrument was vastly deformed due to the tensile force of strings. Takizawa searched all over the globe for a restorer who could repair the instrument without compromising its beautiful toned coloring, but he never found one. Eventually, he decided that it had fulfilled its duties, and wanted to return it to a place where its real value would be appreciated before its beautiful tones were lost. So he asked Takashi Ishii, a violin craftsman in Cremona, to help him donate La Dama to Cremona City, and the Stradivarius Museum decided to acquire and exhibit it. The photo below is of a newspaper article in La Provincia that covered the commemorative concert marking its return. In a speech at the presentation ceremony, Takizawa mentioned why he decided to donate the violin, saying “my instrument wanted to come back to its hometown, Cremona.” The article says that he “explained the reason for the donation in a symbolic way that was unique to the Land of the Rising Sun.”

Takizawa belonged to the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra in 1964, and the concert master of the day was Louis Graeler. I remember he occasionally played chamber music with Graeler in private settings.

A book by Graeler published in Japan (no English edition available) includes an essay titled The Tragedy of Amati in which he says:

When I was a member of NBC Symphony Orchestra, my fellow musician Felix Galmier rushed into the rehearsal room with a pallid face, saying ‘I just saw an instrument I knew at Hermann’s.’ According to him, Alma Rosé, a daughter of a famous quartet player Arnold Josef Rosé, owned the violin. She was captured by the Nazis, but instead of being sent to the gas chamber, she was forced to play music to give solace to the Jewish people who were waiting in line for the gas chamber. She played several times, but could not take it and took her own life.

“La Dama” might be the instrument that had been in the hands of Alma Rosé. It was produced in the age of Vivaldi and J.S. Bach, cherished by a bevy of players, survived WWII, and finally came to Japan.

Since April 2013, a team led by Maestro Giorgio Scolari has been undertaking scientific research to determine whether it is an Amati or not.

ホロヴィッツの遺産

このサイトは20世紀最高のピアニスト「ウラジミール・ホロヴィッツ」に関するサイトである。

2014年11月5日 ホロヴィッツ没後25周年の命日に「ホロヴィッツの遺産」を出版した。本サイトはこの本の内容をアップデートするとともに、載せていない情報も掲載したサイトである。

このサイト・トップにある本は9,700円で販売されている。

本にはホロヴィッツが世界でリリースしたPiano-Roll,78回転盤、45回転盤、LP、CDのすべてがジャケット写真とともに掲載され、VHSテープ、LD,DVD等でリリースされた映像のジャケット写真のすべても掲載されている。

ジャケト写真は1,300枚に及び、コレクター必見の書籍である。

収集の際重複して集めたものは販売しております。

販売サイトはこちら。

ISHIIは1978年から日本で放送されたクラシック音楽番組を

個人的に録画してきた。これはDVD3000枚に及ぶ。

またISHIIはThe Hyper Print Art

と名付けた、新たな芸術分野を開拓したが、これらに関してはISHII and Daughtersをご覧頂きたい。

Mail address of horowitz.jp ishii@horowitz.jp